Would JFK have pulled out of Vietnam ? - Part 1

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PhLlOiWvvXo

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qcr5Q2RfhSQ&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qcr5Q2RfhSQ

|

Decide for Yourself

|

|

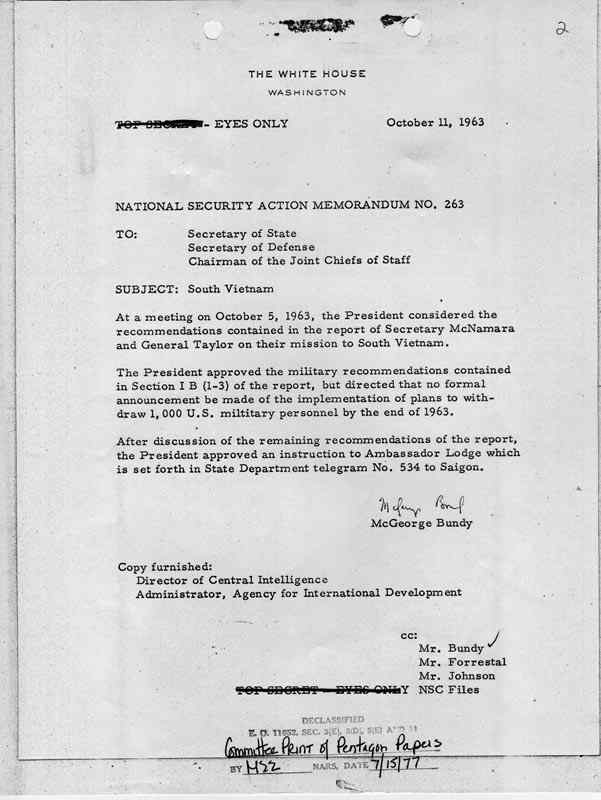

THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON November 26, 1963 NATIONAL SECURITY ACTION MEMORANDUM NO. 273 TO: The Secretary of State The Secretary of Defense The Director of Central Intelligence The Administrator, AID The Director, USIA Here is the audio on Withdrawal from NAM Below The President has reviewed the discussions of South Vietnam which occurred in Honolulu, and has discussed the matter further with Ambassador Lodge. He directs that the following guidance be issued to all concerned: 1. It remains the central object of the United States in South Vietnam to assist the people and Government of that country to win their contest against the externally directed and supported Communist conspiracy. The test of all U. S. decisions and actions in this area should be the effectiveness of their contribution to this purpose. 2. The objectives of the United States with respect to the withdrawal of U. S. military personnel remain as stated in the White House state- ment of October 2, 1963. 3. It is a major interest of the United States Government that the present provisional government of South Vietnam should be assisted in consolidating itself and in holding and developing increased public support. All U.S. officers should conduct themselves width this objective in view. 4. The President expects that all senior officers of the Government will move energetically to insure the full unity of support for established U.S. policy in South Vietnam. Both in Washington and in the field, it is essential that the Government be unified. It is of particular importance that express or implied criticism of officers of other branches be scrupulously avoided in all contacts with the Vietnamese Government and with the press. More specifically, the President approves the following lines of action developed in the discussions of the Honolulu meeting, of November 20. The offices of the Government to which central responsibility is assigned are indicated in each case. (page 1 of 3 pages) Page 2 November 26, 1963 5. We should concentrate our own efforts, and insofar as possible we should persuade the Government of South Vietnam to concentrate its efforts, on the critical situation in the Mekong Delta. This concentra- tion should include not only military but political, economic, social, educational and informational effort. We should seek to turn the tide not only of battle but of belief, and we should seek to increase not only the control of hamlets but the productivity of this area, especially where the proceeds can be held for the advantage of anti-Communist forces. (Action: The whole country team under the direct supervision of the Ambassador.) 6. Programs of military and economic assistance should be maintained at such levels that their magnitude and effectiveness in the eyes of the Vietnamese Government do not fall below the levels sustained by the United States in the time of the Diem Government. This does not exclude arrangements for economy on the MAP account with respect to accounting for ammunition, or any other readjustments which are possible as between MAP and other U. S. defense resources. Special attention should be given to the expansion of the import, distribution, and effective use of fertilizer for the Delta. (Action: AID and DOD as appropriate. ) 7. Planning should include different levels of possible increased activity, and in each instance there should be estimates of such factors as: A. Resulting damage to North Vietnam; B. The plausibility of denial; C. Possible North Vietnamese retaliation; D. Other international reaction. Plans should be submitted promptly for approval by higher authority. (Action: State, DOD, and CIA. ) 8. With respect to Laos, a plan should be a developed and submitted for approval by higher authority for military operations up to a line up to 50 kilometers inside Laos, together with political plans for minimizing the international hazards of such an enterprise. Since it is agreed that operational responsibility for such undertakings should (page 2 of 3 pages) Page 3 November 26, 1963 pass from CAS to MACV, this plan should include a redefined method of political guidance for such operations, since their timing and character can have an intimate relation to the fluctuating situation in Laos. (Action: State, DOD, and CIA.) 9. It was agreed in Honolulu that the situation in Cambodia is of the first importance for South Vietnam, and it is therefore urgent that we should lose no opportunity to exercise a favorable influence upon that country. In particular a plan should be developed using all available evidence and methods of persuasion for showing the Cambodians that the recent charges against us are groundless. (Action: State.) 10. In connection with paragraphs 7 and 8 above, it is desired that we should develop as strong and persuasive a case as possible to demonstrate to the world the degree to which the Viet Cong is controlled, sustained and supplied from Hanoi, through Laos and other channels. In short, we need a more contemporary version of the Jorden Report, as powerful and complete as possible.

(Action: Department

of State with other agencies as necessary.)

s/ McGeorge Bundy McGeorge Bundy cc: Mr. Bundy Mr. Forrestal Mr. Johnson NSC Files (page 3 of 3 pages) [DECLASSIFIED - was classified TOP SECRET Auth: EO 11652 Date: 6-8-76 By: Jeanne W. Davis NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL ]

NSAM

288 (Below

NOW, LET'S GO BACK TO 1954.

JFK-NAM-1954

The

Truth About

April 6, 1954

Mr. President,

the time has come for the American people to be told the blunt truth

about

I am reluctant

to make any statement which may be misinterpreted as unappreciative

of the gallant French struggle at Dien Bien Phu and elsewhere; or as

partisan criticism of our Secretary of State just prior to his

participation in the delicate deliberations in

But to pour

money, material, and men into the jungles of

Despite this

series of optimistic reports about eventual victory, every member of

the Senate knows that such victory today appears to be desperately

remote, to say the least, despite tremendous amounts of economic and

materiel aid from the

I am frankly of

the belief that no amount of American military assistance in

Moreover,

without political independence for the Associated States, the other

Asiatic nations have made it clear that they regard this as a war of

colonialism; and the "united action" which is said to be

so desperately needed for victory in that area is likely to end up

as unilateral action by our own country. Such intervention, without

participation by the armed forces of the other nations of Asia,

without the support of the great masses of the people of the

Associated States, with increasing reluctance and discouragement on

the part of the French--and, I might add, with hordes of Chinese

Communist troops poised just across the border in anticipation of

our unilateral entry into their kind of battleground--such

intervention, Mr. President, would be virtually impossible in the

type of military situation which prevails in Indochina.

This is not a

new point, of course. In November of 1951, I reported upon my return

from the

"In

In June of last

year, I sought an amendment to the Mutual Security Act which would

have provided for the distribution of American aid, to the extent

feasible, in such a way as to encourage the freedom and independence

desired by the people of the Associated States My amendment was

soundly defeated on the grounds that we should not pressure France

into taking action on this delicate situation; and that the new

French government could be expected to make "a decision which

would obviate the necessity of this kind of amendment or

resolution." The distinguished majority leader [Mr. Knowland]

assured us that "We will all work, in conjunction with our

great ally,

Every year we

are given three sets of assurances: First, that the independence of

the Associated States is now complete; second, that the independence

of the Associated States will soon be completed under steps

"now" being undertaken; and, third, that military victory

for the French Union forces in Indochina is assured, or is just

around the corner, or lies two years off. But the stringent

limitations upon the status of the Associated States as sovereign

states remain; and the fact that military victory has not yet been

achieved is largely the result of these limitations. Repeated

failure of these prophecies has, however, in no way diminished the

frequency of their reiteration, and they have caused this nation to

delay definitive action until now the opportunity for any desirable

solution may well be past.

It is time,

therefore, for us to face the stark reality of the difficult

situation before us without the false hopes which predictions of

military victory and assurances of complete independence have given

us in the past. The hard truth of the matter is, first, that without

the wholehearted support of the peoples of the Associated States,

without a reliable and crusading native army with a dependable

officer corps, a military victory, even with American support, in

that area is difficult if not impossible, of achievement; and,

second, that the support of the people of that area cannot be

obtained without a change in the contractual relationships which

presently exist between the Associated States and the French Union.

If the French

persist in their refusal to grant the legitimate independence and

freedom desired by the peoples of the Associated States; and if

those peoples and the other peoples of Asia remain aloof from the

conflict, as they have in the past, then it is my hope that

Secretary Dulles, before pledging our assistance at Geneva, will

recognize the futility of channeling American men and machines into

that hopeless internecine struggle.

The facts and

alternatives before us are unpleasant, Mr. President. But in a

nation such as ours, it is only through the fullest and frankest

appreciation of such facts and alternatives that any foreign policy

can be effectively maintained. In an era of supersonic attack and

atomic retaliation, extended public debate and education are of no

avail, once such a policy must be implemented. The time to study, to

doubt, to review, and revise is now, for upon our decisions now may

well rest the peace and security of the world, and, indeed, the very

continued existence of mankind. And if we cannot entrust this

decision to the people, then, as Thomas

VIETNAM (PULLOUT) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l3Icbzk8mg8 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UN6r7MTTf9Y Thank Gil Jesus for the following>>>

Even the GI's knew it through the

"Stars and Stripes".

I didn't know this...: Contact Information tomnln@cox.net Good Day.... FYI.... THE BEGINNING OF NAM Possible reason

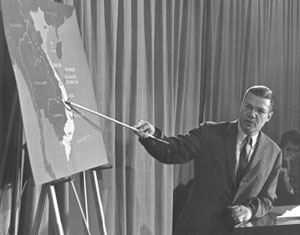

When John F. Kennedy inherited the responsibility of the presidency he also inherited the wars that banking and the military industrial complex were heavily invested in promoting and profiting from. Presidents Truman and Eisenhower had subsidized the French war against Vietnam under the auspices of the Marshall Plan from 1948 to 1952, giving France five billion two hundred million dollars in military aid. By 1954, the U.S. was paying approximately 80% of all French war costs. In 1951 the Rockefeller Foundation had created a study group comprised of members from the Council on Foreign Relations and England's Royal Institute on International Affairs. The panel concluded that there should be a British-American takeover of Vietnam as soon as possible. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles one of the CFR founders and his brother, CIA Director Allen Dulles and many others immediately championed the council's goals. Vietnam had fought against the French occupation since 1884. By 1947 Vietnam was considered a valuable colony to be exploited by both French and American interests. In the countryside, peasants struggled under heavy taxes and high rents. In corporate factories, coalmines, and rubber plantations the people labored under abysmal conditions barely able to survive. The Vietnamese people rose up against the poverty and enslavement imposed upon them and fought the powerful French Foreign Legion, which was funded by America, and in 1954 the Vietnamese people took back their country. With the ejection of the French, the Geneva Agreements were signed on July 21,1954, officially ending the hostilities in Indochina. The agreement prohibited foreign troops and arms from entering Vietnam, and stipulated that free Democratic elections were to be held in 1956, allowing the people of Vietnam to determine their country's future. South Vietnam's corrupt Prime Minister Diem was completely opposed to the Geneva Agreements, and the elections. CIA research had proven that if free democratic elections were held, Diem would lose and Vietnam would become a unified country. France and America would loose their slave colony and the profitable Vietnam War venture would end. The Dulles brothers urged Eisenhower to intervene militarily, and invade Vietnam, but Eisenhower refused. The potential for arms production profits from an Asian country divided by civil war were staggering, particularly if the war could be made to last twenty years or more. Allen Dulles acting independently from President Eisenhower, with the support of Clarence Dillon's son Douglas, Averell Harriman, Prescott Bush and many others sent 675 covert military operatives into Vietnam headed by Air Force officer Edward Lansdale. Their mission was to help Diem stop fair and democratic elections and to prevent the establishment of a united Vietnam. The National Security Council's planning board assured Diem that if hostilities resulted, United States' armed forces would help him oppose the North Vietnamese. With the backing of America, the dictatorial Diem claimed that his government had never signed the Geneva Agreements and was not bound by them, and he promptly cancelled the elections. In 1958 Civil War started, and within two years guerrilla war erupted throughout Southern Vietnam. Diem asked Washington for assistance which resulted in yet another profitable war for America's military industrialists. Dean Rusk (Secretary of State) and Robert McNamara (Secretary of Defense) hounded Kennedy into sending 10,000 Special Forces troops to Vietnam between 1961 and 1962. Kennedy was privately and publicly against the Vietnam War created by the military industrial complex. He didn't buy into their manufactured propaganda about the worldwide communist menace. Kennedy said, "I can not justify sending American boys half-way around the world to fight communism when it exists just south of Florida in Cuba." Kennedy stressed that Diem needed to win the hearts and minds of his people in the struggle against communism. Kennedy said, "I don't think that unless a greater effort is made by the Government to win the popular support that the war can be won out there. In the final analysis, it is their war. They are the ones who have to win it or lose it". Kennedy knew that only with all of the South Vietnamese people fully behind him could Diem hope to defeat the North. Diem ignored Kennedy's advice and behaved like a dictator and his heavy-handed tactics continuously eroded the support of his people. America's ten thousand soldiers and a constant rain of bombs proved to be inconsequential in the effort to suppress the Vietnamese population. Allen Dulles, Dean Rusk, and Robert McNamara kept the truth about the deteriorating Vietnam situation hidden from Kennedy. The military industrial power structure surrounding Kennedy would only say that the war was going exactly as planned, that the Vietnamese people were being liberated, and that they liked Prime Minister Diem. Kennedy had reasons to doubt their word, as he had caught Allen Dulles covertly attempting to train a second group of Cuban exiles for another Cuban invasion. Kennedy had sent FBI agents in to destroy Dulles's training camps and confiscate the weapons, letting the matter end there. Kennedy no longer trusted the Dulles brothers, Rusk, McNamara or Dean Acheson, his so-called Democratic foreign policy advisor, or for that matter, most of the people in the corrupt government he had inherited. Kennedy decided that he needed to monitor the Vietnam War and the men conducting it more closely. He formed a panel, appointing Allen Dulles and others to keep him apprised on a constant basis as to the status of the war. On March 13, 1962, the Northwoods document was brought to Kennedy's attention. The Joint Chiefs of Staff and Allen Dulles had drawn up a plan to launch a series of terrorist attacks within the United States, combined with a media blitz blaming Cuba for the attacks. They believed this would frighten the American public into overwhelmingly supporting a second invasion of Cuba. The Northwoods plan called for Pentagon and CIA paramilitary forces to sink ships, hijack airliners and bomb buildings. When Kennedy heard of their plan, he was furious. The corrupt military industrial power structure within the American government knew no bounds, not even the lives of their own countrymen mattered in their quest for power and profit. Kennedy removed CIA director Allen Dulles, deputy director Richard Bissell and General Lyman Lemnitzer, head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, for their parts in the plan. Within weeks Prescott Bush who had close dealings with these individuals, chose to retire prematurely from politics for supposed health reasons. Kennedy realized that the CIA was a focal point of corporate war planning, from which emanated a secret agenda that threatened the security and freedom of the American people. He said, "I will shatter the CIA into a thousand pieces and scatter them to the winds". Kennedy intended to do battle with a terrible evil and take America back from the military industrial complex and those who financed it. He began by founding a panel that would investigate the CIA's numerous crimes. He put a damper on the breadth and scope of the CIA, limiting their ability to act under National Security Memorandum 55. With the CIA temporarily under control he turned his attention to the task of gathering real information on the war by sending McNamara and Taylor- an aide he trusted, to Vietnam. Based on their memo entitled, Report of McNamara-Taylor Mission to South Vietnam, Kennedy decided that America needed to withdraw immediately from the unwinnable and immoral Vietnam War. Kennedy personally helped draft the final version of a report wherein it stated; "The Defense Department should announce in the very near future presently prepared plans to withdraw 1000 U.S. military personnel by the end of 1963." Kennedy soon issued National Security Action Memorandum 263, and forty pages in the Gravel Pentagon Papers that were devoted to the withdrawal plan. With this new Memorandum Kennedy began to implement the removal of U.S. forces from Vietnam. Many individuals in the U.S. government were CFR members, an organization that was openly pushing the Vietnam War, and these same people had close ties to the privately owned Federal Reserve banking system, a chief financial promoter and profiteer of war. Kennedy intended to stop the Vietnam War and all future wars waged for profit by America. He intended to regain control of the American people's government and their country by cutting off the military industrial complex and Federal Reserve banking system's money supply. Kennedy launched his brilliant attack using the Constitution, which states "Congress shall have the Power to Coin Money and Regulate the Value." Kennedy stopped the Federal Reserve banking system from printing money and lending it to the government at interest by signing Executive Order 11,110 on June 4, 1963. The order called for the issuance of $4,292,893,815 (4.3 trillion) in United States Notes through the U.S. treasury rather than the Federal Reserve banking system. He also signed a bill backing the one and two-dollar bills with gold which added strength to the new government issued currency. Kennedy's comptroller James J. Saxon, encouraged broader investment and lending powers for banks that were not part of the Federal Reserve system. He also encouraged these non-Fed banks to deal directly with and underwrite state and local financial institutions. By taking the capital investments away from the Federal Reserve banks, Kennedy would break them up and destroy them. It was at this time that the corrupt politicos and CFR members, representatives of organizations who stood to profit most from the Vietnam War and loose the most from the Federal Reserve deconstruction, revealed themselves publicly as a group against President Kennedy. They were all considered the pillars of right wing American establishment and their protests and accusations became more bellicose after initial troop withdrawal plans were announced on November 16, 1963. The Council on Foreign Relations, the Morgan and Rockefeller interests and the CIA had been extensively intertwined for years in promoting the Vietnam War and other wars, and their motives were the same. Kennedy was facing the fight of his young life against a group of wealthy powerful bankers and industrialists who had their representatives deeply implanted within American Government and business. The names of some of these people and the organizations they represented were: • Nelson

Rockefeller - New York Governor Prime Minister Diem was loosing control of South Vietnam and growing impatient with the American war. He had begun negotiations with Ho Chi Minh, leader of the North, which unlike the Vietnamese election could not be prevented or rigged. A potential unification might occur quickly. The Vietnam War moneymaking engine was in grave danger from both the actions of Diem and Kennedy. The military industrial complex had their cadre Henry Cabot Lodge conveniently positioned within the US State Department and the Kennedy administration as a Vietnam War advisor and U.S. Ambassador to Saigon. Lodge made secret arrangements with CIA operatives in Vietnam to have Diem assassinated on November 2, 1963. Kennedy had not authorized such an order and after Diem's assassination he immediately instituted an investigation to find out who was responsible. Ten days later on November 12, 1963 Kennedy publicly stated, in a speech delivered to hundreds of students and teachers at Columbia University; "The high office of the President has been used to foment a plot to destroy the American people's freedom, and before I leave office, I must inform the citizens of this plight." Eight days later on November 20, 1963 Vietnam War advisor Walt Whitman Rostow was somehow granted a personal meeting with Kennedy to attempt to sell him on the Vietnam War with a plan he called "a well-reasoned case for a gradual escalation". Kennedy had already rejected a similar plan to escalate the war in 1961, he had publicly announced his own plan of withdrawal from the war, but the corrupt power structure wouldn't accept it. The meeting was Kennedy's last chance. Two days after rejecting Rostow's transparent plan for war, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, who alone had dared to stand against the military industrial complex and the Federal Reserve banking system, was murdered in Dallas, Texas at 12:30 p.m. CST on November 22, 1963, in a bloody "coup d'état". On that day America ceased to be a democracy of, by, and for the people. From that day forward the leaders of the American government have only been the willing puppets of corporations and an international banking cartel that profits from war. The day after Kennedy's brutal murder, the 23rd of November 1963, CIA director John McCone personally delivered the pre-prepared National Security Memorandum #278 to the White House. The handlers of newly installed President Lyndon B. Johnson needed to modify the policy lines of peace pursued by Kennedy. Classified document #278, reversed John Kennedy's decision to de-escalate the war in Vietnam by negating Security Action Memorandum 263, and the Gravel Pentagon Papers. The issuance of Memorandum 278 gave the Central Intelligence Agency immediate funding and approval to sharply escalate the Vietnam conflict into a full-scale war. On November 29, 1963 Johnson created the Warren Commission to investigate the assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy, the 35th President of the United States. Publicly he directed the Commission to evaluate all the facts and circumstances surrounding the assassination and the subsequent killing of the alleged assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald. It had been prearranged among members of the commission, those with connections to the industrial and banking cartel, that there would only be one conclusion, Oswald must be seen as the lone assassin. Incredibly, Allen Dulles, the man who hated Kennedy for not backing his Bay of Pigs fiasco, and for stopping his Northwoods plan, and dismissing him as head of the CIA, was appointed to the Warren commission to preview all evidence gathered by the CIA and FBI and determine what the other commission members would be allowed to see! Some of the information that Dulles may have prevented the other commission members from seeing was a couple of internal FBI memos from J. Edgar Hoover’s office, which raise far more questions than they answer. The first memo dated 1:45 PM November 22, (an hour and fifteen minutes after Kennedy’s murder) states that: “Mr. GEORGE H.W. BUSH, President of the Zapata Off-shore Drilling Company, Houston, Texas, residence 5525 Briar, Houston, furnished the following information to writer by long distance telephone call from Tyler, Texas. (approximately 90 miles from Dallas where Kennedy was murdered, a fast one hour drive) BUSH stated that he wanted to be kept confidential, but wanted to furnish hearsay that he recalled hearing in recent weeks, the day and source unknown. He stated that one JAMES PARROTT has been talking of killing the President when he comes to Houston.” The other memo states that: “An informant who has furnished reliable information in the past and who is close to a small pro-Castro group in Miami has advised that these individuals are afraid that the assassination of the President may result in strong repressive measures being taken against them and, although pro-Castro in their feelings, regret the assassination. The substance of the following information was orally furnished by George Bush of the Central Intelligence Agency and Captain William Edwards of the Defense Intelligence Agency on November 23, 1963" (the day after Kennedy’s Murder) George H.W. Bush made his temporary exit from the CIA, soon after the Kennedy murder, and in 1964 ran as a Goldwater Republican for Congress, campaigning against the 'Civil Rights Act' and the 'Nuclear Test Ban Treaty'. He stated in his campaign speeches that America should arm Cuban exiles and aid them in the overthrow of Castro. He denounced the United Nations and said the Democrats were "too soft" on Vietnam. He recommended that South Vietnam be given nuclear weapons to use against North Vietnam. Although Bush had powerful backers like, 'Oil Men for Bush', who agreed with his apocalyptic visions, the American voters were not yet ready for Bush's brand of fascist extremism and he lost the election. In 1966 Bush ventured forth again as a political candidate, toning down the apocalyptic rhetoric. He ran as a moderate Republican and was elected to the first of two terms in the House of Representatives from the 7th District of Texas. In 1970 Bush lost a Senate race to Lloyd Bentsen. It was not the end of his political career, but rather the redirection of it. A recognized soldier among the corporate military industrial elite, he was destined for a position of power when the time was right and when America had been dragged far enough to the right. In the interim, his wealthy friends kept him busy working behind the scenes in a number of appointments: UN Ambassador for Nixon in 1971, GOP national chair in 1973, and special envoy to China in 1974. On January 27, 1973, in spite of American saturation bombings during the peace talks, the United States, North Vietnam, South Vietnam and the National Liberation Front's provisional revolutionary government signed a peace agreement. The treaty stipulated the immediate end of hostilities and the withdrawal of U.S. and allied troops. The US involvement in the Vietnam 'slaughter for profit war' had lasted 25 years and resulted in 3,000,000 Vietnamese and 58,000 Americans killed. $570 billion taxpayer dollars were consumed in the war, generating obscene profits for the Federal Reserve banking system and the military industrial complex. "Dynasty of Death" (Part 1) http://www.thepeoplesvoice.org/cgi-bin/blogs/voices.php/2006/10/05/dynasty_of_death_part_1 Reference information: http://demopedia.democraticunderground.com http://www.democraticunderground.com/discuss/duboard.php?az=view_all&address=104x5456280 http://inquirer.gn.apc.org/bush_story.html -###- © Copyright October 10, 2006 by Schuyler Ebbets. This article is posted on http://www.thepeoplesvoice.org Permission is granted for reprint in print, email, blog, or web media if this credit is attached and the title remains unchanged.

|

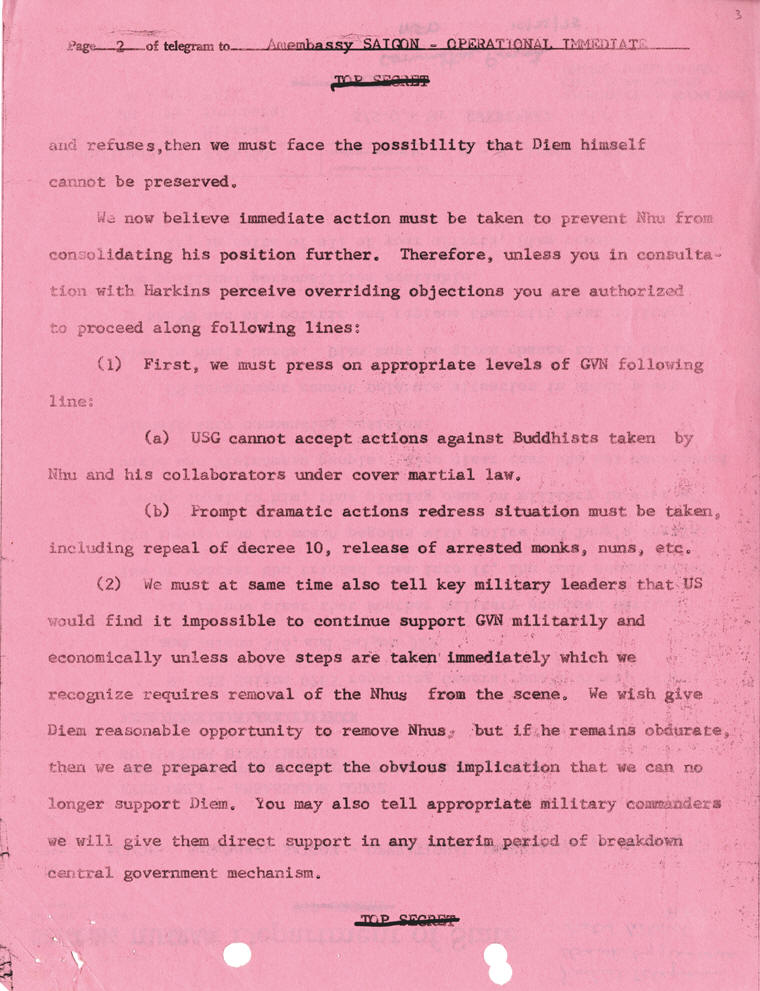

The Kennedy Assassination and the Vietnam War (1971)Peter Dale ScottExcerpts from TextWith respect to events in November 1963, the bias and deception of the original Pentagon documents are considerably reinforced in the Pentagon studies commissioned by Robert McNamara. Nowhere is this deception more apparent than in the careful editing and censorship of the Report of a Honolulu Conference on November 20, 1963, and of National Security Action Memorandum 273, which was approved four days later. Study after study is carefully edited so as to create a false illusion of continuity between the last two days of President Kennedy’s presidency and the first two days of President Johnson’s. The narrow division of the studies into topics, as well as periods, allows some studies to focus on the “optimism”[1] which led to plans for withdrawal on November 20 and 24, 1963; and others on the “deterioration” and “gravity”[2] which at the same meetings led to plans for carrying the war north. These incompatible pictures of continuous “optimism” or “deterioration” are supported generally by selective censorship, and occasionally by downright misrepresentation. …National Security Action Memorandum 273, approved 26 November 1963. The immediate cause for NSAM 273 was the assassination of President Kennedy four days earlier; newly-installed President Johnson needed to reaffirm or modify the policy lines pursued by his predecessor. President Johnson quickly chose to reaffirm the Kennedy policies… Emphasis should be placed, the document stated, on the Mekong Delta area, but not only in military terms. Political, economic, social, educational, and informational activities must also be pushed: “We should seek to turn the tide not only of battle but of belief…” Military operations should be initiated, under close political control, up to within fifty kilometers inside of Laos. U.S. assistance programs should be maintained at levels at least equal to those under the Diem government so that the new GVN would not be tempted to regard the U.S. as seeking to disengage. The same document also revalidated the planned phased withdrawal of U.S. forces announced publicly in broad terms by President Kennedy shortly before his death: “The objective of the United States with respect to withdrawal of U.S. military personnel remains as stated in the White House statement of October 2, 1963.” No new programs were proposed or endorsed, no increases in the level or nature of U.S. assistance suggested or foreseen…. The emphasis was on persuading the new government in Saigon to do well those things which the fallen government was considered to have done poorly…NSAM 273 had, as described above, limited cross-border operations to an area 50 kilometers within Laos.[3] The reader is invited to check the veracity of this account of NSAM 273 against the text as reproduced below. If the author of this study is not a deliberate and foolish liar, the some superior had denied him access to the second and more important page of NSAM 273, which “authorized planning for specific covert operations, graduated in intensity, against the DRV,” i.e., North Vietnam.[4] As we shall see, this covert operations planning soon set the stage for a new kind of war, not only through the celebrated 34A Operations which contributed to the Tonkin Gulf incidents, but also through the military’s accompanying observations, as early as December 1963, that “only air attacks” against North Vietnam would achieve these operations’ “stated objective.”[5] Leslie Gelb, the Director of the Pentagon Study Task Force and the author of the various and mutually contradictory Study Summaries notes that, with this planning, “A firebreak had been crossed, and the U.S. had embarked on a program that was recognized as holding little promise of achieving its stated objectives, at least in its early stages.”[6] We shall argue in a moment that these crucial and controversial “stated objectives,” proposed in CINCPAC’s OPLAN 34-63 of September 9, 1963, were rejected by Kennedy in October 1963, and first authorized by the first paragraph of NSAM 273. The Pentagon studies, supposedly disinterested reports to the Secretary of Defense, systematically mislead with respect to NSAM 273, which McNamara himself had helped to draft. Their lack of bona fides is illustrated by the general phenomenon that (as can be seen from our Appendix A), banal or misleading paragraphs (like 2, 3, and 5) are quoted verbatim, sometimes over and over, whereas those preparing for an expanded war are either omitted or else referred to obliquely. The only study to quote a part of the paragraph dealing with North Vietnam does so from subordinate instructions: it fails to note that this language was authorized in NSAM 273.[7] And study after study suggest (as did press reports at the time) that the effect of NSAM 273, paragraph 2, was to perpetuate what Mr. Gelb ill-advisedly calls “the public White House promise in October” to withdraw 1,000 U.S. troops.[8] In fact the public White House statement on October 2 was no promise, but a personal estimate attributed to McNamara and Taylor. As we shall see, Kennedy’s decision on October 5 to implement this withdrawal (a plan authorized by NSAM 263 of October 11), was not made public until November 16, and again at the Honolulu Conference of November 20, when an Accelerated Withdrawal Program (about which Mr. Gelb in silent) was also approved.[9] NSAM 273 was in fact approved on Sunday, November 24, and its misleading opening paragraphs (including the meaningless reaffirmation of the “objectives” of the October 2 withdrawal statement) were leaked to selected correspondents.[10] Mr. Gelb, who should have known better, pretended that NSAM 273 “was intended primarily to endorse the policies pursued by President Kennedy and to ratify provisional decisions reached (on November 20) in Honolulu.”[11] In fact the secret effect of NSAM … was to annul the NSAM 263 withdrawal decision announced four days earlier at Honolulu, and also the Accelerated Withdrawal Program: “both military and economic programs, it was emphasized, should be maintained at levels as high as those in the time of the Diem regime.”[12] The source of this change is not hard to pinpoint. Of the seven people known to have participated in the November 24 reversal of the November 20 withdrawal decisions, five took part in both meetings.[13] Of the three new officials present, the chief was Lyndon Johnson, in his second full day and first business meeting as President of the United States.[14] The importance of this second meeting, like that of the document it approved, is indicated by its deviousness. Once can only conclude that NSAM 273(2)’s public reaffirmation of an October 2 withdrawal “objective,” coupled with 273(6)’s secret annulment of an October 5 withdrawal plan, was deliberately deceitful. The result of the misrepresentations in the Pentagon studies and Mr. Gelb’s summaries is, in other words, to perpetuate a deception dating back to NSAM 273 itself. This deception, I suspect, involved far more than the symbolic but highly sensitive issue of the 1,000-man withdrawal. One study, after calling NSAM 273 a “generally sanguine” “don’t-rock-the-boat document,” concedes that it contained “an unusual Presidential exhortation”: “The President expects that all senior officers of the government will move energetically to insure full unity of support for establishing U.S. policy in South Vietnam.”[15] In other words, the same document which covertly changed Kennedy’s withdrawal plans ordered all senior officials not to contest or criticize this change. This order had a special impact on one senior official: Robert Kennedy, an important member of the National Security Council (under President Kennedy) who was not present when NSAM 273 was rushed through the forty-five minute “briefing session” on Sunday, November 24. It does not appear that Robert Kennedy, then paralyzed by the shock of his bother’s murder, was even invited to the meeting. Chester Cooper records that Lyndon Johnson’s first National Security Council meeting was not convened until Thursday, December 5.[16] NSAM 273, Paragraph 1: The Central ObjectWhile noting that the “stated objectives” of the new covert operations plan against North Vietnam were unlikely to be fulfilled by the OPLAN itself, Mr. Gelb, like the rest of the Pentagon Study authors, fails to inform us what these “stated objectives” were. The answer lies in the “central object” or “central objective” defined by the first paragraph of NSAM 273: It remains the central object of the United States in South Vietnam to assist the people and Government of that country to win their contest against the externally directed and supported communist conspiracy. The test of all U.S. decisions and actions in this area should be the effectiveness of their contribution to this purpose.[17] To understand this bureaucratic prose we must place it in context. Ever since Kennedy came to power, but increasingly since the Diem crisis and assassination, there had arisen serious bureaucratic disagreement as to whether the U.S. commitment in Vietnam was limited and political (“to assist”) or open-ended and military (“to win”). By its use of the word “win,” NSAM 273, among other things, ended a brief period of indecision and division, when indecision itself was favoring the proponents of a limited (and political) strategy, over those whose preference was unlimited (and military).[18] In this conflict the seemingly innocuous word “object” or “objective” had come, in the Aesopian double-talk of bureaucratic politics, to be the test of a commitment. As early as May 1961, when President Kennedy was backing off from a major commitment in Laos, he had willingly agreed with the Pentagon that “The U.S. objective and concept of operations” was “to prevent Communist domination of South Vietnam.”[19] In November 1961, however, Taylor, McNamara, and Rusk attempted to strengthen this language, by recommending that “We now take the decision to commit ourselves to the objective of preventing the fall of South Vietnam to Communism.”[20] McNamara had earlier concluded that this “commitment…to the clear objective” was the “basic issue,” adding that it should be accompanied by a “warning” of “punitive retaliation against North Vietnam.” Without this commitment, he added, “We do not believe major U.S. forces should be introduced in South Vietnam.”[21] Despite this advice, Kennedy, after much thought, accepted all of the recommendations for introducing U.S. units, except for the “commitment to the objective” which was the first recommendation of all. NSAM 111 of November 22, 1962, which became the basic document for Kennedy Vietnam policy, was issued without this first recommendation.[22] Instead he sent a letter to Diem on December 14, 1961, in which “the U.S. officially described the limited and somewhat ambiguous extent of its commitment:…our primary purpose is to help your people….We shall seek to persuade the Communists to give up their attempts of force and subversion.’”[23] One compensatory phrase of this letter (“the campaign…supported and directed from the outside”) became (as we shall see) a rallying point for the disappointed hawks in the Pentagon; and was elevated to new prominence in NSAM 273(1)’s definition of a Communist “conspiracy.” It would appear that Kennedy, in his basic policy documents after 1961, avoided any used of the word “objective” that might be equated to a “commitment.” The issue was not academic: as presented by Taylor in November 1961, this commitment would have been open-ended, “to deal with any escalation the communists might choose to impose.”[24] In October 1963, Taylor and McNamara tried once again: by proposing to link the withdrawal announcement about 1,000 men to a clearly defined and public policy “objective” of defeating communism. Once again Kennedy, by subtle changes of language, declined to go along. His refusal is the more interesting when we see that the word and the sense he rejected in October 1963 (which would have made the military “objective” the overriding one) are explicitly sanctioned by Johnson’s first policy document, NSAM 273. (See table p. 321.) A paraphrase of NSAM 273’s seemingly innocuous first page was leaked at the time by McGeorge Bundy to the Washington Post and the New York Times. As printed in the Times by E.W. Kenworthy this paraphrase went so far as to use the very words, “overriding objective,” which Kennedy had earlier rejected.[25] This tribute to the words’ symbolic importance is underlined by the distortion of NSAM 273, paragraph 1, in the Pentagon Papers, so that the controversial words “central object” hardly ever appear.[26] Yet at least two separate studies understand the “object” or “objective” to constitute a “commitment”: “NSAM 273 reaffirms the U.S. commitment to defeat the VC in South Vietnam.”[27] This particular clue to the importance of NSAM 273 in generating a policy commitment is all the more interesting, in that the Government edition of the Pentagon Papers has suppressed the page on which it appears.