Dallas District Attorney

Testimony at bottom;

The Same Henry Wade who LOST the "Wade vs. Roe Case on Abortion.

The Same Henry Wade who once served as head of the Chicago FBI.

The same Henry Wade who stood next to Jack Ruby at the midnight press conference.

Jack Ruby was also from Chicago.

On Friday night when Henry misspoke saying that Oswald was a member of the "Free Cuba Committee (an Anti-Castro Group run by the CIA), It was Jack Ruby who corrected him by shouting out "No Henry, that's the "Fair Play For Cuba Committed". (Pro-Castro)

WHY did the authorities LIE when they said they had NO Tape Recorder?

|

After

A strapping 6-footer with a square jaw and a

half-chewed cigar clamped between his teeth, The Chief, as he was known,

prosecuted Jack Ruby. He was the Wade in Roe v. Wade. And he compiled a

conviction rate so impressive that defense attorneys ruefully called

themselves the 7 Percent Club. But now, seven years after Wade's death, The

Chief's legacy is taking a beating.

Nineteen convictions ‹ three for murder and the rest involving rape

or burglary ‹ won by Wade and two successors who trained under him have

been overturned after DNA evidence exonerated the defendants. About 250

more cases are under review. No other county in Current District Attorney Craig Watkins, who in

2006 became the first black elected chief prosecutor in any "There was a cowboy kind of mentality and

the reality is that kind of approach is archaic, racist, elitist and

arrogant," said Watkins, who is 40 and never worked for Wade or met

him. 'Not a racist' "My father was not a racist. He didn't have

a racist bone in his body," said Kim Wade, a lawyer in his own right.

"He was very competitive." Moreover, former colleagues ‹ and even the

Innocence Project of Texas, which is spearheading the DNA tests ‹ credit

Wade with preserving the evidence in every case, a practice that allowed

investigations to be reopened and inmates to be freed. (His critics say,

of course, that he kept the evidence for possible use in further

prosecutions, not to help defendants.) The new DA and other Wade detractors say the

cases won under Wade were riddled with shoddy investigations, evidence was

ignored and defense lawyers were kept in the dark. They note that the

promotion system under Wade rewarded prosecutors for high conviction

rates. In the case of James Lee Woodard ‹ released in

April after 27 years in prison for a murder DNA showed he didn't commit

‹ Wade's office withheld from defense attorneys photographs of tire

tracks at the crime scene that didn't match Woodard's car. "Now in hindsight, we're finding lots of

places where detectives in those cases, they kind of trimmed the corners

to just get the case done," said Michelle Moore, a 'Win at all costs' "When someone was arrested, it was assumed

they were guilty," he said. "I think prosecutors and

investigators basically ignored all evidence to the contrary and decided

they were going to convict these guys." A Democrat, Wade was first elected DA at age 35

after three years as an assistant DA, promising to "stem the rising

tide of crime." Wade already had spent four years as an FBI agent,

served in the Navy during World War II and did a stint as a local

prosecutor in nearby He was elected 10 times in all. He and his cadre

of assistant DAs ‹ all of them white men, early on ‹ consistently

reported annual conviction rates above 90 percent. In his last 20 years as

district attorney, his office won 165,000 convictions, the Dallas Morning

News reported when he retired. In the 1960s, Wade secured a murder conviction

against Ruby, the Wade was also the defendant in the 1973 landmark

Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision legalizing abortion. The case began

three years earlier when Cases overturned Lenell Geter, a black engineer, was convicted of

armed robbery and sentenced to life in prison. After Geter had spent more

than a year behind bars, Wade agreed to a new trial, then dropped the

charges in 1983 amid reports of shoddy evidence and allegations Geter was

singled out because of his race. In Wade's final year in office, the U.S. Supreme

Court overturned the death sentence of a black man, Thomas Miller-El,

ruling that blacks were excluded from the jury. Cited in Miller-El's

appeal was a manual for prosecutors that Wade wrote in 1969 and was used

for more than a decade. It gave instructions on how to keep minorities off

juries. A month before Wade died of Parkinson's disease

in 2001, DNA evidence was used for the first time to reverse a Watkins, a former defense lawyer, has since put

in place a program under which prosecutors, aided by law students, are

examining hundreds of old cases where convicted criminals have requested

DNA testing. 'Protecting a legacy' "I think the number of examples of cases

show it's troubling," said Nina Morrison, an attorney with the

Innocence Project, a New York-based legal group affiliated with the Former assistant prosecutor Dan Hagood said The

Chief expected his assistants to be prepared, represent the state well and

be careful and fair. "Never once ‹ ever ‹ did I ever get the

feeling of anything unethical," Hagood said. He denied there was any

pressure exerted from above ‹ "no `wink' deals, no `The boss says

we need to get this guy.'" But Watkins said those who defend The Chief are

"protecting a legacy." "Clearly it was a culture. A lot of folks

don't want to admit it. It was there," the new DA said. "We

decided to fix it." |

WADE OVERTURNED

After Dallas DA's Death,

19 Convictions Are Undone

DALLAS - As district attorney of Dallas for an unprecedented 36 years, Henry Wade was the embodiment of Texas justice.

A strapping 6-footer with a square jaw and a half-chewed cigar clamped between his teeth, The Chief, as he was known, prosecuted Jack Ruby. He was the Wade in Roe v. Wade. And he compiled a conviction rate so impressive that defense attorneys ruefully called themselves the 7 Percent Club.

But now, seven years after Wade's death, The Chief's legacy is taking a beating.

Henry Wade

Nineteen convictions ‹ three for murder and the rest involving rape or burglary ‹ won by Wade and two successors who trained under him have been overturned after DNA evidence exonerated the defendants. About 250 more cases are under review.

No other county in America ‹ and almost no state, for that matter ‹ has freed more innocent people from prison in recent years than Dallas County, where Wade was DA from 1951 through 1986.

Current District Attorney Craig Watkins, who in 2006 became the first black elected chief prosecutor in any Texas county, said that more wrongly convicted people will go free.

"There was a cowboy kind of mentality and the reality is that kind of approach is archaic, racist, elitist and arrogant," said Watkins, who is 40 and never worked for Wade or met him.

'Not a racist'

But some of those who knew Wade say the truth is more complicated than Watkins'

summation.

"My father was not a racist. He didn't have a racist bone in his body," said Kim Wade, a lawyer in his own right. "He was very competitive."

Moreover, former colleagues ‹ and even the Innocence Project of Texas, which is spearheading the DNA tests ‹ credit Wade with preserving the evidence in every case, a practice that allowed investigations to be reopened and inmates to be freed. (His critics say, of course, that he kept the evidence for possible use in further prosecutions, not to help defendants.)

The new DA and other Wade detractors say the cases won under Wade were riddled with shoddy investigations, evidence was ignored and defense lawyers were kept in the dark. They note that the promotion system under Wade rewarded prosecutors for high conviction rates.

In the case of James Lee Woodard ‹ released in April after 27 years in prison for a murder DNA showed he didn't commit ‹ Wade's office withheld from defense attorneys photographs of tire tracks at the crime scene that didn't match Woodard's car.

"Now in hindsight, we're finding lots of places where detectives in those cases, they kind of trimmed the corners to just get the case done," said Michelle Moore, a Dallas County public defender and president of the Innocence Project of Texas. "Whether that's the fault of the detectives or the DA's, I don't know."

'Win at all costs'

John Stickels, a University of Texas at Arlington criminology professor and a

director of the Innocence Project of Texas, blames a culture of "win at all

costs."

"When someone was arrested, it was assumed they were guilty," he said. "I think prosecutors and investigators basically ignored all evidence to the contrary and decided they were going to convict these guys."

A Democrat, Wade was first elected DA at age 35 after three years as an assistant DA, promising to "stem the rising tide of crime." Wade already had spent four years as an FBI agent, served in the Navy during World War II and did a stint as a local prosecutor in nearby Rockwall County, where he grew up on a farm, the son of a lawyer. Wade was one of 11 children; six of the boys went on to become lawyers.

He was elected 10 times in all. He and his cadre of assistant DAs ‹ all of them white men, early on ‹ consistently reported annual conviction rates above 90 percent. In his last 20 years as district attorney, his office won 165,000 convictions, the Dallas Morning News reported when he retired.

In the 1960s, Wade secured a murder conviction against Ruby, the Dallas nightclub owner who shot Lee Harvey Oswald after Oswald's arrest in the assassination of President Kennedy. Ruby's conviction was overturned on appeal, and he died before Wade could retry him.

Wade was also the defendant in the 1973 landmark Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision legalizing abortion. The case began three years earlier when Dallas resident Norma McCorvey ‹ using the pseudonym Jane Roe ‹ sued because she couldn't get an abortion in Texas.

Cases overturned

Troubling cases surfaced in the 1980s, as Wade's career was winding down.

Lenell Geter, a black engineer, was convicted of armed robbery and sentenced to life in prison. After Geter had spent more than a year behind bars, Wade agreed to a new trial, then dropped the charges in 1983 amid reports of shoddy evidence and allegations Geter was singled out because of his race.

In Wade's final year in office, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the death sentence of a black man, Thomas Miller-El, ruling that blacks were excluded from the jury. Cited in Miller-El's appeal was a manual for prosecutors that Wade wrote in 1969 and was used for more than a decade. It gave instructions on how to keep minorities off juries.

A month before Wade died of Parkinson's disease in 2001, DNA evidence was used for the first time to reverse a Dallas County conviction. David Shawn Pope, found guilty of rape in 1986, had spent 15 years in prison.

Watkins, a former defense lawyer, has since put in place a program under which prosecutors, aided by law students, are examining hundreds of old cases where convicted criminals have requested DNA testing.

'Protecting a legacy'

Of the 19 convictions that have been overturned, all but four were won during

Wade's tenure. In two-thirds of the cases, the defendants were black men. None

of the convictions that have come under review are death penalty cases.

"I think the number of examples of cases show it's troubling," said Nina Morrison, an attorney with the Innocence Project, a New York-based legal group affiliated with the Texas effort. "Whether it's worse than other jurisdictions, it's hard to say. It would be a mistake to conclude the problems in these cases are limited to Dallas or are unique to Dallas.

Former assistant prosecutor Dan Hagood said The Chief expected his assistants to be prepared, represent the state well and be careful and fair.

"Never once ‹ ever ‹ did I ever get the feeling of anything unethical," Hagood said. He denied there was any pressure exerted from above ‹ "no `wink' deals, no `The boss says we need to get this guy.'"

But Watkins said those who defend The Chief are "protecting a legacy."

"Clearly it was a culture. A lot of folks don't want to admit it. It was there," the new DA said. "We decided to fix it."

© 2008 MSNBC.com

* * *

Wade,

Henry Volume V page 213-254

TESTIMONY

OF HENRY WADE

Senator COOPER. Will you raise your hand?

Do you solemnly swear the testimony you are about to give this Commission

will be the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, so help you God?

Mr. WADE. I do.

Senator COOPER. You are informed about the purposes of this

investigation.

Mr. WADE. I know it, generally.

Senator COOPER. Do you desire a lawyer?

Mr. WADE. No, sir.

Senator COOPER. Thank you very much.

Mr. RANKIN. Mr. Wade, we are going to ask you generally about the time of

Mr. Oswald's, Lee Harvey Oswald's, arrest, what you had to do in connection with

the entire matter, and the press being there at the jail, and the scene-and

seeing what happened there, and the various things in regard to Mr. Dean and

other witnesses in connection with the matter.

Will you state your name?

Mr. WADE. Henry Wade.

Mr. RANKIN. Where do you live?

Mr. WADE. I am district attorney, or criminal district attorney of

Mr. RANKIN. Will you tell us briefly your qualifications for your

position and profession?

213

Page

214

Mr. WADE. Well, I am a graduate of the

Later I became a lieutenant, junior grade, served in the Pacific 2 years,

about 2 years.

Then after the war I got out of the Navy on the 6th of February 1946, ran

for district attorney in

I was elected district attorney in 1950 and have been criminal district

attorney of

Mr. RANKIN. Have you handled many of the prosecutions of that county

since that time?

Mr. WADE. Well, my office or I have handled all of them since that time.

I have had quite a bit of experience myself.

I have a staff of 41 lawyers and, of course, I don't try all the cases

but I have tried quite a few, I would say 40, 50 anyhow since I have been

district attorney.

Mr. RANKIN. Do you have any particular policy about which cases you would

try generally?

Mr. WADE. Well, it varies according to who my first assistant has been.

It is varied. If I have a

first assistant who likes to try cases, I usually let him try a lot and I do the

administrative. At the present time

I have a very fine administrative assistant, Jim Bowie, whom you met and I try a

few more cases.

I guess I have tried four in the last year probably but two to five a

year are about all the cases I try myself personally.

Mr. RANKIN. Do you have any policy about capital cases as to whether you

should try them or somebody else?

Mr. WADE. I don't try all of them. I

try all the cases that are very aggravated and receive probably some publicity

to some extent, and I don't try all the capital cases.

I think we have had quite a few death penalties but I don't imagine I

have been in over half of them, probably half of them.

Mr. RANKIN. Do you remember where you were at the time you learned of the

assassination of President Kennedy?

Mr. WADE. Well, they were having a party for President Kennedy at Market

Hall and I was out at Market Hall waiting for the President to arrive.

Mr. RANKIN. How did you learn about the assassination?

Mr. WADE. Well, one of the reporters for one of the newspapers told me

there had been a shooting or something, of course, one of those things we were

getting all kinds of rumors spreading through a crowd of 3,000-5,000 people, and

then they got the radio on and the first report was they had killed two Secret

Service agents, that was on the radio, and then the press all came running in

there and then ran out, no one knew for sure what was going on until finally

they announced that President had been shot and from the rostrum there the

chairman of the----

Mr. DULLES. Who was the chairman of that meeting, do you recall?

Mr. WADE. Eric Johnson. Eric

Johnson.

Mr. RANKIN. Was he mayor then?

Mr. WADE. No; he wasn't mayor, he was the president of

Mr. RANKIN. What did you do after you heard of the assassination?

Mr. WADE. Well, the first thing, we were set up in a bus to go from there

to Austin to another party that night for President Kennedy, a group of us, 30

or 40. We got on a bus and went.

I went back to the office and sent my wife home, my wife was with me.

214

Page

215

And the first thing that I did was go check the

law to see whether it was a Federal offense or mine.

I thought it was a Federal offense when I first heard about it.

We checked the law, and were satisfied that was no serious Federal

offense, or not a capital case, anyhow.

There might be

some lesser offense. I talked to the

Mr. RANKIN. Who

was that?

Mr. WADE.

Barefoot Sanders and he was in agreement it was going to be our i case

rather than his and he had been doing the same thing.

Mr. RANKIN. Where did you talk to him?

Mr. WADE. On the telephone as I recall, in his office from my office.

I am not even sure I talked with him, somebody from my office talked to

him, because I think you can realize things were a little confused and that took

us, say, until 3:30 or 4.

I let everybody in the office go home, but some of my key personnel who

stayed there. I let the girls or

told them they could go home, because they did close all the offices down there.

The next thing I did--do you want me to tell you?

Mr. RANKIN. Yes.

Mr. WADE. I will tell you what I can.

The next thing I did was to go by the sheriff's office who is next door

to me and talked to Decker, who is the sheriff.

Bill Decker, and they were interviewing witnesses who were on the streets

at the time, and I asked him and he said they have got a good prospect.

This must have been 3 o'clock roughly.

Mr. RANKIN. The witnesses that were on the street near the

Mr. WADE. Yes, sir; and in the building, I am not sure who they were,

they had two court reporters there taking statements.

Mr. RANKIN. Did they tell you anything about a suspect at that point?

Mr. WADE. The Sheriff told me, he said, "Don't say nothing about it,

but they have got a good suspect," talking about the

He didn't have him there. John

Connally, you know, was shot also--and he was, he used to be a roommate of mine

in the Navy and we were good friends, and are now--and the first thing I did

then was went out to the hospital to see how he was getting along.

I must have stayed out there until about 5 o'clock, and in case you all

don't know or understand one thing, it has never been my policy to make any

investigations out of my office of murders or anything else for that matter.

We leave that entirely to the police agency.

Mr. RANKIN. Do you have a reason for that?

Mr. WADE. That is the way it is set up down there.

We have more than we can do actually in trying the cases.

The only time we investigate them is after they are filed on, indicted,

and then we have investigators who get them ready for trial and then lawyers.

Mr. DULLES. Have you any personnel for that?

Mr. WADE. No, sir; I have in my office 11 investigators but that is just

1 for each court, and they primarily, or at least about all they do is line up

the witnesses for trial and help with jury picking and things of that kind.

Mr. RANKIN. At this point that you are describing, had you learned of any

arrest?

Mr. WADE. No, sir; Mr. Decker says they have a good suspect.

He said that sometime around 3 o'clock.

You see, I didn't have the benefit of all that was on the air.

I didn't even know Oswald had been arrested at this time.

As a matter of fact, I didn't know it at 5 o'clock when I left the

hospital.

When I left the hospital, I went home, watched television a while, had

dinner, and a couple, some friends of ours came over there.

They were going to

At that time they kept announcing they had Oswald or I believe they named

a name.

Mr. RANKIN. Had you learned about the Tippit murder yet?

Mr. WADE. Yes, sir; of course, it had been on the air that Tippit had

been killed.

215

731-221 O---64---vol. V----15

Page

216

I went by the

Mr. RANKIN. Was that unusual for you to do that?

Mr. WADE. It was unusual because I hadn't been in the Dallas Police

Department, I won't be there on the average of once a year actually, I mean on

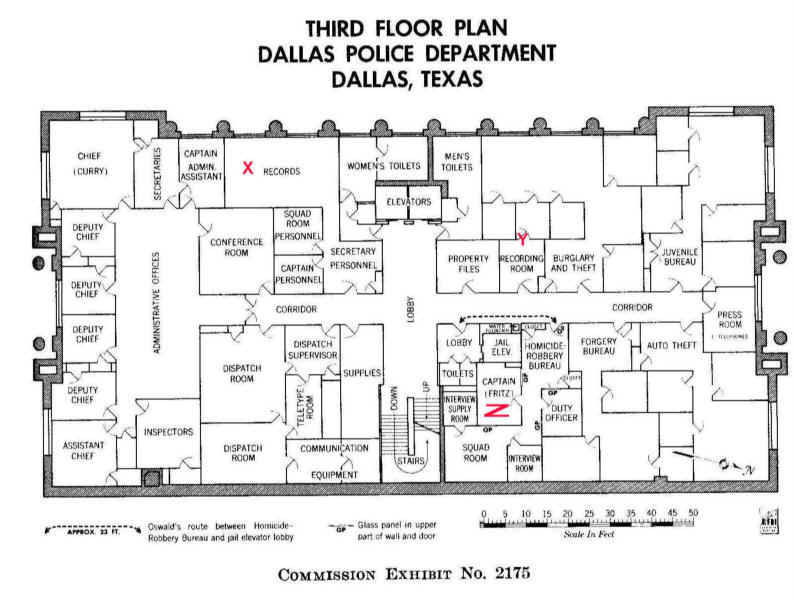

anything. I went by there and I went to Chief Curry's office.

Mr. RANKIN. How did you happen to do that this time?

Mr. WADE. Of course, this is not really, this was not an ordinary case,

this was a little bit different, and I mostly wanted to know how he was coming

along on the investigation is the main reason I went by.

As I went in, and this is roughly 6:30, 7 at night--I said we ate dinner

at home, I believe the couple were out in the car with my wife were waiting for

me to go to dinner with them.

Mr. DULLES. Did you go down to the airfield when President Johnson left?

Mr. WADE. No, sir; no, sir.

Mr. DULLES. You did not.

Mr. WADE. I didn't go anywhere but to my office, then to

Mr. RANKIN. About what time was this at the police station?

Mr. WADE. I would say around 7 o'clock.

This can vary 30 minutes either way.

Mr. RANKIN. Who did you see there?

Mr. WADE. Chief Curry.

Mr. RANKIN. Did you talk to him?

Mr. WADE. I talked to him.

Mr. RANKIN. What did you say to him and what did

he say to you?

Mr. WADE. Well,

it is hard to remember. I know the

first thing he did was pull out a memorandum that you all were interested in,

signed by Jack Revill, and showed it to me and I read it, and said, "What

do you think about that?"

And I said----

Mr. DULLES. I

wonder if you would identify this for the record?

Mr. WADE. You

can get it. Let me tell you the story. I

read that thing there hurriedly and I remember it mentioned that Agenty Hosty

had talked to Revill----

Senator COOPER.

Who was that?

Mr. WADE. Hosty.

Senator COOPER.

Can you identify him as to what he does?

Mr. WADE. He is

a special agent of the FBI, but I don't think I would know him if he walked in

here actually.

But that is his

business. He showed me that, and I

read it. Now, as far as identifying

it, I have seen---I have a copy of it in my files.

You see, when

they turned the records over to me and I read it and looked it over and to the

best of my knowledge was the same memorandum he showed me, although all I did

was glance at it and it said generally they knew something about him and knew he

was in town or something like that.

Senator COOPER.

Who said that?

Mr. WADE This

memorandum said that.

Senator COOPER.

Who is reported to be quoting the memorandum?

Mr. WADE.

Special Agent Hosty. Now, I have

since looked at the memorandum. So

far as I know it is the same memorandum, but like I say I read it there and I

don't know whether it is the--I don't know whether it said word for word to be

the same thing but it appears to me to my best knowledge to be the same

memorandum.

Mr. RANKIN. Do

you know when you first got the memorandum in your files that you are referring

to?

Mr. WADE. It

was a month later. You see the

police gave me a record of everything on the Ruby case, I would say some time

about Christmas.

Mr. RANKIN. I will hand you Commission Exhibit No. 709 and ask you if

that is the memorandum you just referred to?

216

Page

217

Mr. WADE. Yes; to the best of my knowledge that is the memorandum he

showed me there at 7 p.m. on the 22d day of November 1963.

Jack Revill incident.oily, you all have talked with him, but he is one of

the brightest, to my mind, of the young

As a matter of fact, when we got into the Ruby trial, I asked that they

assign Jack Revill to assist us in the investigation and he assisted with

picking of the jury and getting the witnesses all through the Ruby trial.

Mr. RANKIN. Would your records show when you received a copy of this

document, Commission Exhibit No. 709?

Mr. WADE. Well, I am sure it would. It

would be the day--you can trace it back to when the newspapers said he had

turned all the files over to me and it was around Christmas as I recall, and I

believe actually it was after Christmas, but probably 30 days, but you see they

turned over a file that thick to me, I imagine.

It was of all of that, the same thing they turned over to you, everything

the police had on Jack Ruby.

Mr. RANKIN. You put a receipt stamp on anything like that?

Mr. WADE. I don't think it will show a date or anything like that on it

because they just hauled it in there and laid it on my desk.

But this was--it is in our files, and I am rather sure it is the same

time. You all got the same thing.

Mr. RANKIN. We didn't receive anything like that until the time that

Chief Curry came to testify, just for your information.

Mr. WADE. Well, I didn't know that, but now on this, this is the Ruby

matter----

Mr. DULLES. Could I ask one question there?

Mr. WADE. Yes, sir.

Mr. DULLES. Just to refresh my recollection of your testimony, did you

see this that afternoon around 5 or 6 o'clock?

Mr. WADE. Around 7 o'clock I

would say it was on Chief Curry's desk.

Mr. DULLES. Of the 22d?

Mr. WADE. Of the 22d.

Senator COOPER. I don't want

to interrupt too much, but looking at this exhibit, I note it is written, you

have seen this Commission, Commission Exhibit No. 709 signed by Jack Revill?

Mr. WADE. Yes; let me see it; yes.

Senator COOPER. Is your

recollection, was the memorandum that was shown to you by--first, who did show

you the memorandum on the 22d?

Mr. WADE. Chief Curry of the

Senator COOPER. Was the memorandum shown to you on the 22d by Chief Curry

in this same form?

Mr. WADE. To the best of my knowledge that was it now.

Now, like I said I read this memorandum, and I read the memorandum, and

asked the chief what he was going to do with it and he said, "I don't

know."

And then the next morning I heard on television Chief Curry, I don't know

whether I heard him or not, he made some kind of statement concerning this

memorandum on television, and then later came back and said that wasn't to his

personal knowledge, and I think that was--he said that what he said about it he

retracted it to some extent but I guess you all have got records of those

television broadcasts or at least can get them.

Mr. RANKIN. Do you remember whether he said just what was in this Exhibit

No. 709 or something less than that or more or what?

Mr. WADE. I don't remember.

You see, things were moving fast, and it is hard there are so many things

going on. I will go on to my story.

Mr. RANKIN. Yes.

Mr. WADE. I will answer anything, of course.

Mr. RANKIN. You can tell us the rest that you said to Chief Curry and he

said to you at that time, first.

Mr. WADE. I asked him how the case was coming

along and, as a practical matter he didn't know.

You probably have run into this, but there is really a lack of

communication between the chief's office and the captain of detective's office

there in

Mr. RANKIN. You found that to be true.

217

Page

218

Mr. WADE. For every year I have been in the office down there.

And I assume you have taken their depositions.

I don't know what the relations--the relations are better between Curry

and Fritz than between Hanson and Fritz, who was his predecessor.

But Fritz runs a kind of a one-man operation there where nobody else

knows what he is doing. Even me, for instance, he is reluctant to tell me,

either, but I don't mean that disparagingly.

I will say Captain Fritz is about as good a man at solving a crime as I

ever saw, to find out who did it but he is poorest in the getting evidence that

I know, and I am more interested in getting evidence, and there is where our

major conflict comes in.

I talked to him a minute there and I don't believe I talked to Captain

Fritz. One of my assistants was in

Fritz's office. I believe I did walk

down the hall and talk briefly, and they had filed, they had filed on Oswald for

killing Tippit.

Mr. DULLES. Which assistant was that?

Mr. WADE. Bill Alexander. There

was another one of--another man there, Jim Alien, who was my former first

assistant who is practicing law there in

And I know there is no question about his intentions and everything was

good, but he was just a lawyer there, but he had tried many death penalty cases

with Fritz---of Fritz's cases.

But he was there. Your FBI

was there, your Secret Service were there in the homicide.

Mr. RANKIN. Who from the FBI, do you recall?

Mr. WADE. Well, I saw Vince Drain, a special agent that I knew, and Jim

Bookhout, I believe, and there was Mr. Kelley and Mr. Sorrels--Inspector Kelley

of the Secret Service, Sorrels,

I might tell you that also, to give you a proper perspective on this

thing, there were probably 300 people then out in that hall.

You could hardly walk down the hall.

You just had to fight your way down through the hall, through the press

up there.

Mr. RANKIN. Who were they?

Mr. WADE. The television and newsmen.

I say 300, that was all that could get into that hall and to get into

homicide it was a strain to get the door open hard enough to get into the

office.

Mr. RANKIN. Did you say anything to Chief Curry about that?

Mr. WADE. No, sir; I probably mentioned it but I assume you want--whether

I meant he ought to clean them out or not. I

didn't tell him he should or shouldn't because I have absolutely no control over

the police. They are a separate

entity. They have a municipality, and they work under a city manager.

Mr. RANKIN. Did you say anything to Chief Curry about what should be told

the press about investigation, how it was progressing or anything of that kind?

Mr. WADE. Yes; I think that is the brief conversation, that is the last I

talked to Curry that night. I may

have talked to--but that is all I recall. I

left thereafter, and went on out to dinner.

Mr. RANKIN. About what time did you leave?

Mr. WADE. 7, 7:30, something like that.

I got home, say, 9:30 or 10, after eating dinner, and I believe I talked

to the U.S. attorney or at least I saw it come on the radio that they are going

to file on Oswald as part of an international conspiracy in murdering the U.S.

President, and I think I talked to Barefoot Sanders. He called me or I called

him.

Mr. RANKIN. I

wanted to get for the record, Mr. Wade, who would be trying to file like that.

Mr. WADE. I

don't know. All I know it wasn't me.

It was told to me at one time that the justice of the peace said

something about it and another one, one of my assistants, Alexander had said

something about it and I have talked to both of them since and both of them deny

so I don't know who suggested it or anything but it was on the radio and I think

on television.

I know I heard

it and I am not sure where.

218

Page

219

Mr. RANKIN. Can

you tell us whether it was from your office or from a Federal office that such

an idea was developing as far as you know?

Mr. WADE. Well,

on that score it doesn't make any sense at all to me because there is no such

crime in Texas, being part of an international conspiracy, it is just murder

with malice in Texas, and if you allege anything else in an indictment you have

to prove it and it is all surplusage in an indictment to allege anything,

whether a man is a John Bircher or a Communist or anything, if you allege it you

have to prove it.

So, when I

heard it I went down to the police station and took the charge on him, just a

case of simple murder.

Mr. DULLES. Is

that of Tippit or of the President?

Mr. WADE. No;

of the President, and the radio announced Johnston was down there, and

Alexander, and of course other things, and so I saw immediately that if somebody

was going to take a complaint that he is part of an international conspiracy it

had to be a publicity deal rather--somebody was interested in something other

than the law because there is no such charge in Texas as part of--I don't care

what you belong to, you don't have to allege that in an indictment.

Mr. RANKIN. What do you mean by the radio saying that Johnson was there?

Do you mean President Johnson?

Mr. WADE. No; that is the justice of the peace whose name is

Mr. RANKIN. I see.

Mr. WADE. Yes; Justice of the Peace David L. Johnston was the justice of

the peace there.

So, I went down there not knowing--also at that time I had a lengthy

conversation with Captain Fritz and with Jim Alexander who was in the office,

Bill Alexander, Bookhout because another reason I thought maybe they were going

to want to file without the evidence, and then that put everything on me, you

know.

If they didn't have the evidence and they said, "We file on him, we

have got the assassin" I was afraid somebody might take the complaint and I

went down to be sure they had some evidence on him.

Mr. RANKIN. Have you told us all that you said to the

Mr. WADE. So far as I know. I know that concerned that point, you know.

Mr. RANKIN. Well, did he say anything to you about that point?

Mr. WADE. Well, I think he asked me was that--I don't think Barefoot was

real conversant, I guess is the word with what the law is in a murder charge.

I told him that it had no place in it and he said he had heard it on the

radio and didn't know whether it would be thought

it might because some if it was not

necessary, he did not think it ought to be done, something to that effect so I

went down there to be sure they didn't.

I went over the evidence which they--when I saw the evidence, it was the

evidence as told to me by Captain Fritz.

Mr. RANKIN. This conversation you have described you had when Jim

Alexander was there and the others?

Mr. WADE. Yes; I first asked Jim Allen, a man whom I have a lot of

confidence in, do they have a case and he said it looks like a case, you can

try.

Mr. RANKIN. Is that the case about the assassination?

Mr. WADE. Yes; we are talking entirely about the assassination.

On the Tippit thing, I didn't take the charge on that and I think they

had some witnesses who had identified him there at the scene, but I was more

worried about the assassination of them filing on somebody that we couldn't

prove was guilty.

Mr. RANKIN. Did you discuss the evidence that they did have at that time

with Captain Fritz?

Mr. WADE. Yes, sir.

Mr. RANKIN. Will you tell us what evidence you recall?

Mr. WADE. I have made no notes but roughly he gave the story about him

bringing the gun to work, saying it was window rods from the neighbor, someone

who had brought him to work. He also

said there were three employees of the company that left him on the sixth floor.

He told about, the part about,

219

Page

220

the

young officer running in there right after the assassination and Oswald leaving

after the manager said that he was employed there.

Told about his arrest and said that there was a scuffle there, and that

he tried to shoot the officer.

I don't know--I think I am giving you all this because I think a little

of it may vary from the facts but all I know is what Fritz told me.

He said the

They said they had a palmprint on the wrapping paper, and on the box, I

believe there by the scene. They did

at least put Oswald there at the scene.

Mr. RANKIN. Will you clarify the palmprint that you are referring to on

the rifle?

Was it on the underside of the rifle, was it between the rifle and the

stock or where was it as you recall?

Mr. WADE. Specifically, I couldn't say because

but he said they had a palm-print or a fingerprint of Oswald on the

underside of the rifle and I don't know whether it was on the trigger guard or

where it was but I knew that was important, I mean, to put the gun in his

possession.

I thought we had that all the time when I took the complaint on the

thing.

Let me see what else they had that night.

Well, they had a lot of the things they found in his possession. They had

the map, you know, that marked the route of the parade.

They had statements from the bus driver and the taxicab driver that

hauled him somewhere.

I think they varied a little as to where they

picked him up but generally they had some type of statement from them.

That is

generally what they gave me now.

Mr. RANKIN. That is all you recall as of that time?

Mr. WADE. Yes, sir.

Mr. RANKIN. Did you give any report to the press then about----

Mr. WADE. No; I will tell you what happened then.

Mr. RANKIN. Yes, sir.

Mr. WADE. As we walked out of the thing they started yelling, I started

home, and they stared yelling they wanted to see Oswald, the press.

And Perry said that he had put him in the showup room downstairs.

Of course, they were yelling all over the world they wanted a picture of

Oswald.

And I don't know the mob and everybody ended up in the showup room.

It is three floors below there.

Mr. RANKIN. Still Friday night?

Mr. WADE. Yes, sir.

Mr. RANKIN. About what time?

Mr. WADE. I would say around midnight roughly. It would--it could be

either way an hour because I went down there around 11 o'clock, 10:30 or 11,

some roughly and I don't know what the time element was but I would say around

midnight.

So, they started interviewing Fritz and Curry, and I started to leave and

Fritz said, "Well, we will get --" either Fritz or Curry said,

"We will show him up down there," he said, "This is Mr. Wade, the

district attorney."

He kind of introduced me to the press.

I didn't say anything at that time but down in the basement they started

to put Oswald--I went down there with them.

They started to put Oswald in the lineup down there.

Mr. RANKIN. Will you describe that briefly to the Commission?

Mr. WADE. Well, I don't know whether you have seen--it is a room larger

than this and you have a glass here on this side. Behind that glass they have a

place out here where they walk prisoners in through there and you can see

through this side but you can't see through that side. I think that is the way

it is set up.

Senator COOPER. You mean observers can see?

Mr. WADE. Observers can see, but the defendants or suspects can't see

through or at least can't identify.

220

Page

221

Mr. RANKIN. Do you remember

who else besides Lee Harvey Oswald was in the showup?

Mr. WADE. No; I am just telling you about the showup room.

Now, they had had showups on him but I wasn't there at any of those, but

this was, the purpose of this, was to let the press see Oswald, if I understand

it.

And the police were yelling, "Everybody wants to see him, wants a

picture of him." They started

in the screened-in portion and a howl went up that you can't take a picture

through that screen. Then they had a

conference with, among some of them, and the next thing I knew I was just

sitting there upon a little, I guess, elevated, you might say a speaker's stand,

although there were

300

people in the room, you couldn't even actually get out, you know.

Mr. RANKIN. Did they ask you whether they should do this?

Mr. WADE. I don't think I said yea or nay to the thing so far as I know,

because it was--and I actually didn't know what they were doing until, the next

thing I knew they said they were going to have to bring him in there.

Well, I think I did say, "You'd better get some officers in here or

something for some protection on him."

I thought a little about, and I got a little worried at that stage.

So about 12 officers came in and they were

standing around Oswald, and at this time I looked out in the audience and saw a

man out there, later, who turned out to be Jack Ruby. He was there at that

scene.

Mr. RANKIN. How did you happen to pick him out?

Mr. WADE. Well, I don't know. He

had--I had seen the fellow somewhere before, but I didn't know his name, but he

had a pad, and the reason I remember him mostly----

Mr. RANKIN. You mean a scratch pad?

Mr. WADE. He had some kind of scratch pad.

The reason I mentioned him mostly, I will get into him in a minute and

tell you everything about him. He

was out there about 1 minute, I would say, and they took pictures and everything

else and Oswald was here and the cameras were in a ring around him, and as they

left----

Mr. RANKIN. Excuse me. Where

was Ruby from where you told us where Oswald was?

Mr. WADE. Well, he was, I would say, about 12 feet. I am giving a

rough----

Mr. RANKIN. When. you saw him----

Mr. WADE. We went all through this at the trial, and it varied on where

Ruby was, but when I saw him he was about four rows back in the aisle seat,

standing up in the seat.

Mr. RANKIN. Were there press men around him?

Mr. WADE All kinds of press men around him, and also press men 10 deep

between him and Oswald.

Now, one of their--you mentioned the gun awhile ago---one of their

defenses in the trial was if he had a gun, he had a gun there, he could have

killed him if he wanted to. It is

the first I heard him say that he didn't have a gun that you mentioned awhile

ago. So when I got--when they got

through, they started asking him questions, the press.

Senator COOPER. Wait a minute. How

close were the nearest people in the audience to Oswald?

Mr. WADE. I would say they were that far from him.

Senator COOPER. How far is that?

Mr. WADE. Three feet.

Senator COOPER. You mean some of the reporters and photographers were

within 3 feet of him?

Mr. WADE. They were on the ground, they were on the ground, and they were

standing on top of each other, and on top of tables, and I assume in that room

there were 250 people. It was just a

mob scene.

Senator COOPER. I believe I have seen the room.

Isn't it correct that at the end where the showup is held that is an

elevated platform?

Mr. WADE. There is a platform up there where the microphone is.

Senator COOPER. Was he standing up on the platform?

Mr. WADE. No; he was not at the platform.

Senator COOPER. Was he on the floor level?

221

Page

222

Mr. WADE. He was in the floor level in the middle.

If I understand, that was the first or second time I had ever been in the

room.

Senator COOPER. Were there people around him, surrounding him?

Mr. WADE. People were on the floor in front of those desks.

Senator COOPER. But I mean, were they, were people on all sides of him?

Mr. WADE. No; they were all in front of him.

They were all in front of him, and you had a ring of policemen behind

him, policemen on all sides of him. It was just the front where they were, and

that is the way I recall it, but I knew they had a line of policemen behind him,

and the place was full of policemen, because they went up and it turns out later

they got all the police who

were

on duty that night. They were plain

clothes police, most of them, maybe they had a uniform or two, a few of them.

So they started----

Senator COOPER. Excuse me one

moment.

Mr. WADE. Yes, sir.

Senator COOPER. Can I make a

statement? I will have to go to my

office for a few minutes. I hope to

return in about 20 minutes, and I will ask Mr. Dulles to preside in my place,

and I will return.

Mr. WADE. Thank you, sir.

(At this point, Senator Cooper withdrew from the hearing room.)

Mr. DULLES. Proceed.

Mr. RANKIN. Will you proceed?

Mr. WADE. Yes, sir; so they said, "Have you filed on him?"

At that stage, yelling has he been filed on, and I said yes, and filed on

for murder with and they asked Judge Johnston, is there--they asked him

something.

Then they started asking me questions everywhere, from all angles.

Mr. RANKIN. Under your practice, what do you mean by file on him?

Is that something different than an arraignment?

Mr. WADE. Well, of course, it is according to the terminology and what

you mean by arraignment. In

Mr. RANKIN. I see.

You don't bring him before a magistrate?

Mr. WADE. Well, that is called--you can have an examining trial before

the magistrate to see whether it is a bailable matter.

At that time, I don't believe he had been brought before the magistrate,

because I told David Johnston as we left there, I said, "You ought to go up

before the jail and have him brought before you and advise him of his rights and

his right to counsel and this and that," which, so far as I know, he did.

But at that meeting you had two attorneys from

American Civil Liberties

Mr. RANKIN.

Which meeting?

Mr. WADE. That

Friday night meeting, or Friday night showup we had better call it, midnight on

Friday night. I believe it was Greer

Ragio and Professor Webster from SMU. I

saw them there in the hall, and Chief Curry told me that they had been given an

opportunity or had talked with Oswald. I

am not sure. I was under the

impression that they had talked with them but, of course, I didn't see them

talking with him.

Mr. RANKIN.

Did you talk to them about it?

Mr. WADE. Yes;

I told them that he is entitled to counsel, that is what they are interested in

on the counsel situation, and anybody, either them or anybody else could see him

that wanted to.

Mr. RANKIN.

What did they say then?

Mr. WADE. Mr.

Rankin, I will tell you what, there was so much going on I don't remember

exactly. The only thing was I got

the impression they had already talked with them somewhere, but I don't know

whether they told me or the chief told me or what.

Like I say, it was a mob scene there, practically, and they were standing

in the door when I--they were in the meeting there.

Let me get a

little further and go back to--I don't know whether I answered your question and

if I don't it is because I can't, because I don't know--I will tell you what

happened the next day.

Mr. RANKIN. Let's finish with the showup now.

222

Page

223

Mr. WADE. Yes. They asked a

bunch of questions there. I think if

you get a record of my interview that you will find that any of the evidence----

Mr. DULLES. Which interview is that?

Mr. WADE. With the press, midnight, radio, television, and everything

else. I think if you will get a copy of that you will find they asked me lots of

questions about fingerprints and evidence. I refused to answer them because I

said it was evidence in the case. The

only thing that I told them that you might get the impression was evidence but

is really not evidence, I told them that the man's wife

said the man had a gun or something to that effect.

The reason, maybe good or bad, but that isn't admissible in

Mr. RANKIN. At that time, had you filed on the assassination?

Mr. WADE. Yes, sir; we had filed upstairs prior to this.

He had been filed on for murder with malice.

Mr. RANKIN. But he hadn't been brought before the justice of the peace or

magistrate yet on that complaint, had he?

Mr. WADE. The justice of the peace was there in the office and took it in

the homicide. Oswald was in

homicide, also, but he is in a separate office. Like I told you, I never did see

Oswald except in that lineup downstairs. That was the first time I had seen him.

Mr. RANKIN. Was that when you. told the justice of the peace that he

ought to have him before him to tell him his rights and so forth?

Mr. WADE. Yes;

it was some time during that hour. this went on for about an hour down there,

everything.

Well, during

that interview somebody said, and the thing--Oswald belonged to, was he a

Communist, something generally to that effect.

Mr. RANKIN.

They asked you that?

Mr. WADE. I was

asked that. And I said, well, now, I

don't know about that but they found some literature, I understand, some

literature dealing with Free

Mr. DULLES. You

hadn't known him before?

Mr. WADE. I had

never known him, to my knowledge. He

is a man about town, and I had seen him before, because when I saw him in there,

and I actually thought he was a part of the press corps at the time.

Mr. RANKIN. Were any of your assistants or people working for you there

at that showup?

Mr. WADE. I don't believe there were any of them there now.

If there is any of them, it is Alexander, because he is the only one down

there, but I think he is still up in homicide.

I will go further on that, some of my assistants know him, but he was in

my office 2 days before this with a hot check or something where he was trying

to collect a hot check or pay someone. I

think he was trying to pay someone else's hot check off, I don't know what it

was, I didn't see him. He talked to

my check section. I found this out later.

Mr. RANKIN. By "he" you mean----

Mr. WADE. Ruby, Jack Ruby.

Mr. RANKIN. Yes.

Mr. WADE. He was in another office of mine, since this all came out, he

was in there with a bunch of the police, we were trying a case on pornography,

some of my assistants were, and my assistant came in his office during the noon

hour after coming from the court, this was 2 or 3 days before the assassination

and Ruby was sitting there in his office with five or

six Dallas police officers. In fact, he was sitting in my assistant's desk and

he started to sit down and asked who he was and the officer said, "Well,

that is Jacky Ruby who runs the Carousel Club," so he had been down there.

223

Page

224

I don't know

him personally--I mean I didn't know who he was. of these things I had seen the

man, I imagine, but I had no idea who he was, and I will even go further, after

it was over, this didn't come out in the trial, as they left down there, Ruby

ran up to me and he said, "Hi Henry" he yelled real loud. he yelled.

"Hi, Henry," and put his hand to shake hands with me and I shook hands

with him. And he said, "Don't

you know me?" And I am trying

to figure out whether I did or not. And

he said, "I am Jack Ruby, I run the Vegas Club."

And I said, "What are you doing in here?"

It was in the basement of the city hall.

He said, "I know all these fellows."

Just shook his hand and said, "I know all these fellows."

I still didn't know whether he was talking about the press or police all

the time, but he shook his hands kind of like that and left me and I was trying

to get out of the place which was rather crowded, and if you are familiar with

that basement, and I was trying to get out of that hall. And here I heard

someone call "Henry Wade wanted on the phone," this was about 1

o'clock in the morning or about 1 o'clock in the morning, and I gradually get

around to the phone there, one of the police phones, and as I get there it is

Jack Ruby, and station KLIF in Dallas on the phone.

You see, he had gone there, this came out in the trial, that he had gone

over there and called KLIF and said Henry Wade is down there, I will get you an

interview with him.

Mr. RANKIN. Who

is this?

Mr. WADE. KLIF

is the name of the radio station.

You see, I

didn't know a thing, and I just picked up the phone and they said this is so and

so at KLIF and started asking questions.

But that came

out in the trial.

But to show

that he was trying to be kind of the type of person who was wanting to think he

was important, you know.

Mr. RANKIN. Did

you give him an interview over the telephone to KLIF?

Mr. WADE. Ruby?

Mr. RANKIN. No.

Mr. WADE.

I answered about two questions and hung up, but they had a man down there

who later interviewed me before I got out of the building.

But they just asked me had he been filed and one or two things.

Mr. DULLES. It

was a KLIF reporter that you gave this to, not Ruby?

Mr. WADE. Not

Ruby. Ruby was not on the phone, he

had just gone out and called him and handed the phone to me.

I thought I got a call from somebody, and picked it up and it was KLIF on

the phone.

Mr. RANKIN. On

the pornography charge, was Ruby involved in that?

Mr. WADE. No,

sir; I don't know why he was down there, actually.

But there were six or seven police officers, special services of the

Mr. RANKIN. You

have told us all you remember about the showup?

Mr. WADE. I

told you all, and, of course, all I know about it as far as my interview with

the press. You can get more. accurate, actually, by getting a transcript of it

because I don't remember what all was asked, but I do remember the incident with

Ruby and I know I told them that there would be no evidence given out in the

case.

At that time,

most of it had already been given out, however, by someone.

I think by the police.

Now, the next morning, I don't know of anything else until the next

morning. I went to the office about

9 o'clock.

Mr. DULLES. Could I ask a question?

Mr. WADE. Yes, sir.

(Discussion off the record.)

Mr. RANKIN. Do you have any Particular transcript that you are speaking

about?

224

Page

225

Mr. WADE. No; I don't have anything.

The thing about it is this was taken, this was on television and radio

and all the networks. They had

everything there set up and that is the only--that is the first of, I think,

three times I was interviewed, but it was Friday night around between 12 and 1

o'clock. It was actually Saturday

morning between 12 and 1.

Mr. RANKIN. So there were a number of networks, possibly, and a number of

the radio stations and television stations from the whole area?

Mr. WADE. The whole area and it actually wasn't set up for an interview

with me. It was an interview, what I

thought, with Fritz and Carry, and I thought I would stay for it, but when they

got into the interviewing, I don't know what happened to them but they weren't

there. They had left, or I was the

one who was answering the questions about things I didn't know much about, to

tell you the truth.

Has that got it cleared? Can

I go to the next morning?

I will try to go a little and not forget anything.

The next morning I went to my office, probably, say, 9 o'clock Saturday

morning. Waiting there for me was

Robert Oswald, who was the brother of Lee Harvey Oswald. You probably have met

him, but I believe his name is Robert is his brother.

I talked to him about an hour.

Mr. RANKIN. What did you say to him and what did he say to you?

Mr. WADE. Well, we discussed the history of Lee Harvey Oswald and the one

of the purposes he came to me, he wanted his mother, Oswald's mother, and wife

and him to see Oswald.

Mr. RANKIN. Did he say this

to you?

Mr. WADE. Yes; but we had already set it up, somebody, I don't know

whether my office or the police, but he was set up to see him that morning at 11

o'clock, I believe, or 12 o'clock, some time.

Mr. RANKIN. Did you do anything about it?

Mr. WADE. Yes, sir; I checked to see if it was arranged.

I called Captain Fritz and told him that he wanted to see him, and he

said they were going to let him see him. I

don't know. I don't know the name,

but it was either 11 o'clock or 12 o'clock Saturday morning.

I don't know whether he had requested or not, but that was the first time

I had seen him. I don't know why he

came to my office, but I used it to try to go into Lee Harvey Oswald's

background some, and I also told him that there is a lot involved in this thing

from a national point of view, and I said, "You appear to be a good

citizen," which he did appear to me, "and I think you will render your

country a great service if you will go up and tell Oswald to tell us all about

the thing." That was part of

the deal of my working for a statement from Oswald which didn't pan out, of

course. Because I was going to

interview Oswald Sunday afternoon when we got him into the county jail and I was

going to attempt to get a statement from him.

Mr. RANKIN. Did Robert tell you anything about Lee Harvey Oswald's

background at that time?

Mr. WADE. He told me about in Europe, how in Russia, how they had had

very little correspondence with them and he wrote to them renouncing or telling

them he wanted to renounce his American citizenship and didn't want to have

anything else to do with him. He

said later that one of the letters changed some, I mean back, and then he said

he was coming home, coming back and he had married and kind of his general

history of the thing and he came back and I believe stayed with this Robert in

Fort Worth for 2, 3, or 4 months. Now I say this is from memory, like I don't

have and they had helped him some,

and said that Marina, the thing that impressed her was most your super-markets,

I think, more than anything else in this country, your A. & P. and the big,

I guess you call them, supermarkets or whatever they are.

And he told me something about him going to

Now, it seemed to me like it was a year, and he said their families, they

didn't have anything in common much, and he said, of course

I said "Do you think"--

225

Page

226

I

said, "the evidence is pretty strong against your brother, what do you

think about it?" He said,

"Well, he is my brother. and I hate to think he would do this."

He said, "I want to talk to him and ask him about it."

Now, I never did see him. Roughly,

that is about all I remember from that conversation.

We rambled around for quite a bit.

I know I was impressed because he got out and walked out the front of my

office and in front of my office there were 15 or 20 press men wanting to ask

him something, and he wouldn't say a word to them, he just walked off.

I told him they would be out there, and he said, "I won't have

anything to say."

Mr. DULLES. Was this the morning after the assassination?

Mr. WADE. Yes, sir; Saturday morning.

Mr. DULLES. About what time?

Mr. WADE. I would say between 9 and 10 is when I talked with him.

And so the main purpose in the office, we believed, the main purpose of

me and the lawyers in the office were briefing the law on whether to try Oswald

for the murder of the President, whether you could prove the flight and the

killing of Officer Tippit, which we became satisfied that we could, I mean from

an evidentiary point of view.

Mr. RANKIN. By "we" who do you mean, in your office?

Mr. WADE. Well, I think I had seven or eight in there, Bowie, and

Alexander, and Dan Ellis, Jim Williamson, but there was a legal point.

My office was open, but that, with reference to this case, there were

other things going on, but in reference to this case, this is what we spent our

time trying to establish whether that would be admissible or not.

Mr. RANKIN. Did you consult with any Federal

officers in regard to how you should handle the case or what you should say

about it at any time?

Mr. WADE. No; I

didn't discuss, consult with any of them. I did talk to some of the FBI boys and

I believe there was an inspector.

Mr. RANKIN. Secret Service?

Mr. WADE. No.

Mr. RANKIN. FBI?

Mr. WADE. There was an inspector of the FBI who called me two or three

times. I don't remember.

Mr. RANKIN. Did they tell you how to handle the case in any way?

Mr. WADE. I don't think so. I

mean it wasn't really up to them.

Mr. RANKIN. The only time you

ever talked to Barefoot Sanders about it was in regard to this conspiracy,

possibility of, that you have already described?

Mr. WADE. Frankly, that is

hard to say. I think we talked off

and on every day or two about developments in it, because, you see, well, I

don't know whether we talked any more but before the killing by Ruby, but we had

nearly a daily conversation about the files in the Oswald case, what we were

going to do with them. You see, they

were going to give them all to me, and at that stage we didn't know whether it

was going to be a President's Commission or a congressional investigation or

what. After the President's

Commission was set up, I arranged through him and Miller here in the Justice

Department that rather than give the files to me, to get the police to turn them

over to the FBI and send them to you all, or photostat them and send them to you

all.

Barefoot and I talked frequently, but I don't know of anything

significant of the Oswald angle that we discussed, and we spent the last 2

months trying to get some of the FBI files to read on the Ruby trial.

I mean we talked a lot but I don't know anything further about Oswald

into it or anything on Ruby of any particular significance.

Mr. RANKIN. Was Barefoot Sanders suggesting how you should handle the

Oswald case except the time you already related?

Mr. WADE. I don't recall him doing, suggesting that.

Mr. RANKIN. Any other Federal officers suggesting anything like that to

you?

Mr. WADE The only thing I remember is the

inspector of the FBI whom I don't think I ever met. I was there in the police

one time during this shuffle, and I think it was some time Saturday morning, and

he said they should have nothing, no publicity on the thing, no statements.

Now, I don't

know whether that was after Ruby shot Oswald or before,

226

Page

227

I

don't know when it was, but I did talk with him and I know his concern which was

that there was too much publicity.

Mr. RANKIN.

And he told you that, did he?

Mr. WADE. At

some stage in it. I am thinking it

was Sunday night which I know I talked with him Sunday night, but we are not

that far along with it yet. But I

don't know whether I talked to him previously or not.

Mr. RANKIN. That is the only conversation of that type that you recall

with any Federal officer?

Mr. WADE. That is all I recall. I am sure Barefoot and I discussed the

publicity angle on it some, but I don't remember Barefoot suggesting how we

handle it, but neither one of us knew whether it was his offense or mine, to

begin with, for 2 or 3 hours because we had to select it.

Mr. RANKIN. Do you know what Barefoot said about publicity when you did

discuss it with him?

Mr. WADE. I don't recall anything.

Mr. RANKIN. All right.

What happened next, as you recall?

Mr. WADE. I was going home. I

went by the police station to talk to Chief Curry.

Mr. RANKIN. Did you discuss the evidence then?

Mr. WADE. Well, at that time You

see, Chief Curry knew very little of the evidence at that stage. He should have

known, but he didn't But I discussed the thing with him and I told him there was

too much evidence being put out in the case from his department, that I wish he

would talk to Fritz and have no further statements on it.

Mr. RANKIN. What did he say about that?

Mr. WADE. He said, "That is fine.

I think that is so."

Mr. RANKIN. Now, going back just a moment, you

spoke out about a map earlier that you had been told they had as evidence, do

you recall, of the parade route. Did

you look at the map at the time?

Mr. WADE. I

don't think I ever saw the map.

Mr. RANKIN. You

don't know what it contained in regard to the parade route?

Mr. WADE. I was

told by Fritz that it had the parade route and it had an X where the

assassination took place and it had an X out on Stemmons Freeway and an X at

Inwood Road and Lemon, is all I know, a circle or some mark there.

Mr. RANKIN. But

you have never seen the map?

Mr. WADE. So

far as I know, I have never seen the map. I

don't know even where it was found, but I think it was found in his home,

probably. But that is my recollection. But

I don't even know that. I told Chief

Curry this.

Then I walked out, and Tom Pettit of NBC said, "We are all confused

on the law, where we are really on this thing."

Mr. RANKIN. What did you say?

Mr. WADE. At that time I said, "Well, I will explain the procedure,

Texas procedure in a criminal case," and I had about a 10-minute interview

there as I was leaving the chief's office, dealing entirely with the procedure,

I mean your examining trial and grand jury and jury trial, I mean as to what

takes place. You see, they had all

kinds of statements and other countries represented and they were all curious to

ask legal questions, when bond would be set and when it would be done.

Mr. RANKIN. Did you discuss the evidence at that time?

Mr. WADE. No, sir; I refused. You

will find that I refused to answer questions. They all asked questions on it,

but I would tell them that is evidence and that deals with evidence in the

matter.

Mr. RANKIN. Did you tell them why you wouldn't answer those questions?

Mr. WADE. I told them we had to try the case, here, and we would have to

try the case and we wouldn't be able to get a jury if they knew all the evidence

in the case.

You will find that in those interviews most, I think.

I haven't seen them. As a

matter of fact, didn't see them myself even.

But I went home that day, and----

Mr. DULLES. That day is Saturday?

Mr. WADE. Saturday; yes, sir.

227

Page

228

Mr. RANKIN. About what time?

Do you recall?

Mr. WADE. I

guess I got home 2:30 probably. I must have eaten on the way home or somewhere.

Mr. RANKIN. In

the afternoon?

Mr. WADE. Yes,

sir; and I know I was amazed as I walked through the television room there and

saw Chief Curry with that gun. You

see, at that time they had not identified the gun as his gun, but he was telling

about the report on it.

Mr. RANKIN. Will you just describe what you saw

there at that time?

Mr. WADE. Well,

I know he was in a crowd, and it seems to me like he had the gun, but on second

thought I am not even sure whether he had the gun, but he was tracing the

history of how that the gun was bought under the name, under an assumed name

from a mail-order house in Chicago and mailed there to Dallas, and that the

serial number and everything that had been identified, that the FBI had done

that, something else.

I believe they

said they had a post office box here, a blind post office box that the

recipients of that had identified as Oswald as the guy or something that

received it.

In other words,

he went directly over the evidence connecting him with the gun.

Mr. RANKIN. You

say there was a crowd there. Who was

the crowd around him?

Mr. WADE.

Newsmen. You see, I was at home.

I was watching it on television.

Mr. RANKIN. I

see. Did you do anything about that,

then? Did you call him and ask him

to quit that?

Mr. WADE No; I

felt like nearly it was a hopeless case. I

know now why it happened. That was

the first piece of evidence he got his hands on before Fritz did.

Mr. RANKIN. Will you explain what you mean by that?

Mr. WADE. Well, this went to the FBI and came to him rather than to

Captain Fritz, and I feel in my own mind that this was something new, that he

really had been receiving none of the original evidence, that it was coming

through Fritz to him and so this went from him to Fritz, you know, and I think

that is the reason he did it.

So I stayed home that afternoon. I

was trying to think, it seems like I went back by the police station some time

that night, late at night.

Mr. RANKIN. This way of giving evidence to the press and all of the news

media, is that standard practice in your area?

Mr. WADE. Yes; it is, unfortunately.

I don't think it is good. We

have just, even since this happened we have had a similar incident with the

police giving all the evidence out or giving out an oral confession of a

defendant that is not admissible in court. You

know, oral admissions are not generally admissible in

Mr. RANKIN. Have you done anything about it, tried to stop it in any way?

Mr. WADE. Well, in this actually, in the same story they quoted me as

saying, I mean the news quoted me as saying they shouldn't give the information

out, that is the evidence, we have got to try the case, we will get a jury, it

is improper to do this, or something to that effect.

So far as taking it up with--I have mentioned many ,times that they

shouldn't give out evidence, in talking to the police officers, I mean in there

in training things, but it is something I have no control over whatever.

It is a separate entity, the city of Dallas is, and I do a little fussing

with the police, but by the same token it. is not a situation where

I think it is one of your major problems that are going to have to be

looked into not only here but it is a sidelight, I think, to your investigation

to some extent, but I think you prejudice us, the state, more than you do the

defense by giving out our testimony.

You may think that giving out will help you to convict him.

I think it works the other way, your jurors that read, the good type of

jurors, get an opinion one way or another from what they read, and you end up

with poor jurors. If they haven't

read or heard anything of the case---well, not generally the same type of juror.

The only thing I make a practice of saying is

that I reviewed the evidence in

228

Page

229

this

case in which the State will ask the death penalty, which may be going too far,

but I tell them we plan to ask the death penalty or plan to ask life or plan to

ask maximum jail sentence or something of that kind.

Mr. RANKIN. Did you say that at any time about the Oswald case?

Mr. WADE. Oh, yes, sir; I have said that about both Oswald and Ruby.

Mr. RANKIN. When did you say it about the Oswald case?

Mr. WADE. I guess it was Friday night probably.

I was asked what penalty we would ask for.

Mr. RANKIN. When the police made these releases about the evidence, did

they ever ask you whether they should make them?

Mr. WADE. No, sir; like I told you, I talked Saturday morning around

between 11 and 12, some time, I told him there was entirely too much publicity

on this thing, that with the pressure going to be on us to try it and there may

not be a place in the United States you can try it with all the publicity you

are getting. Chief Curry said he agreed with me, but, like I said about 2 hours

later, I saw him releasing this testimony.

Mr. RANKIN. Did you consult any State officials about how you should

handle either the Oswald or the Ruby ease?

Mr. WADE. I don't know. It

seems like I talked. to Waggoner Carr that night, but I don't remember.

Didn't we talk some time about it?

I don't know whether it was consulting about how to try it or anything.

But I know I talked to Waggoner's office some time within 2 or 3 days,

but I don't know whether it was before the Ruby assault or not.

But he doesn't actually----

Mr. RANKIN. Does the

Mr. WADE. No, sir; I think Waggoner will agree with that.

They don't have any jurisdiction to try criminal cases other than

antitrust, but I assume we would ask for their assistance if we wanted it.

We don't generally, and I don't, the law doesn't contemplate that.

Mr. RANKIN. Mr. Carr didn't try to tell you in any way how to handle

either case?

Mr. WADE. Not that I know of.

Mr. CARR. Off the record.

(Discussion off the record.)

Mr. DULLES. May we proceed.

Mr. RANKIN. Mr. Wade, will you give us the substance of what Mr. Carr

said to you and what you said to him at that time?

Mr. WADE. All I remember--I don't actually

remember or know what night it was I talked to him but I assume it was that

night because he did mention that the rumor was out that we were getting ready

to file a charge of Oswald being part of an international conspiracy, and I told

him that that was not going to be done.

It was late at night and I believe that is----

Mr. DULLES. It must have been Saturday night, wasn't it?

Mr. WADE. No; that was Friday night.

Mr. DULLES. Friday night.

Mr. WADE. And I told him, and then I got a call, since this happened, I

talked to Jim Bowie, my first assistant who had talked to, somebody had called

him, my phone had been busy and Barefoot Sanders, I talked to him, and he they

all told that they were concerned about their having received calls from

Washington and somewhere else, and I told them that there wasn't any such crime

in Texas, I didn't know where it came from, and that is what prompted me to go

down and take the complaint, otherwise I never would have gone down to the

police station.

Mr. RANKIN. Did you say anything about whether you had evidence to

support such a complaint of a conspiracy?

Mr. WADE. Mr. Rankin, I don't know what evidence we have, we had at that

time and actually don't know yet what all the evidence was.

I never did see, I was told they had a lot of Fair Play for

229

Page

230

I was told this. I have never seen any of that personally.

Never saw any of it that night. But

whether he was a Communist or whether he wasn't, had nothing to do with solving

the problem at hand, the filing of the charge.

I also was very, I wasn't sure I was going to take a complaint, and a

justice of the peace will take a complaint lots of times because he doesn't have

to try it. I knew I would have to try this case and that prompted me to go down

and see what kind of evidence they had.

Mr. RANKIN. Will you tell us what you mean by taking a complaint under

your law.

Mr. WADE. Well, a complaint is a blank form that you fill out in the

name, by the authority of the State of Texas, and so forth, which I don't have

here, but it charged, it charges a certain person with committing a crime, and

it is filed in the justice court.

The law permits the district attorney or any of his assistants to swear

the witness to the charge. The only

place we sign it is over on the left, I believe sworn to and subscribed to

before me, this is the blank day of blank, Henry Wade, district attorney.

Over on the right the complainant signs the complaint.