The president

BY THURSTON CLARKE

Elaine de Kooning's attempt to capture the essence of John F. Kennedy in the vivid colors and broad brush strokes of abstract art resulted in the striking portrait that is on permanent exhibit in the Hall of Presidents at the National Portrait Gallery. The story of how she came to paint it is even more extraordinary, and illustrates why capturing Kennedy on a canvas or in a book can be so challenging, and such an obsession, for artists, biographers and historians.

The trustees of the Truman Library chose de Kooning to paint the notoriously restless Kennedy because she had a reputation for being 'the fastest brush in the East,' capable of finishing a portrait after a single sitting. When she arrived at the Kennedy family's Palm Beach estate on Dec. 31, 1962, she planned on making some quick sketches before finishing the portrait in a temporary studio in West Palm Beach. She had expected, she said, the monochrome man of the newspaper photographs.

Instead, Kennedy struck her as 'incandescent, golden,' 'bigger than life' and inhabiting 'a different dimension.' After a single morning she decided that he was too intriguing and changeable to capture in one portrait. She stayed for four days, drawing dozens of sketches, charcoals and watercolors, and working on several oil portraits at once.

She returned to New York with her sketches and portraits, and soon there were more, many more. During 1963 she drew and painted only Kennedy, sketching him when he appeared on television and clipping photographs from newspapers and magazines that she used as models for more drawings and oils.

After running out of space in her studio, she papered her living quarters with more sketches and photographs, so that whenever she cooked, ate or took a bath, she saw him. When Kennedy's friend Bill Walton visited her studio in early November 1963 - a few weeks before Dallas - he found 38 oil portraits in various stages of completion leaning against walls or sitting on easels.

I can sympathize. Anyone visiting my office while I was completing JFK's Last Hundred Days would have come across a similar scene. I had started with one bookshelf with 40 books - memoirs by members of Kennedy's inner circle; biographies of JFK, Jackie, Teddy, Bobby and Rose. Within months I had five bookshelves and more than 300 books. I crammed eight file cabinets with cop-

.See JFK, 4P

A president of many, many boxes

ies of oral-history transcripts and copies of documents.

I bought two long trestle tables that I covered with files chronicling what he had done and said on each of his last 100 days in office. I listened to his news conferences (he gave one every 16 days, on average); watched his home movies; bought the books he read during these last days, and read them; and photocopied the newspapers he read, and read those, too.

I did all this for the same reason de Kooning spent a year attempting to distill Kennedy's essence into a single painting - because like many others who have written about him, I was gripped by the challenge of creating a definitive portrait of one of the most complicated, secretive, elusive and enigmatic men ever to occupy the White House, and of solving what I consider the greatest Kennedy mystery of all: not who killed him 50 years ago, but who he was when he died.

Even those who knew Kennedy well have spoken about the seeming impossibility of knowing him in his entirety. Ted Sorensen, his principal aide and speechwriter, believed that 'different parts of his life, work, and thoughts were seen by many people - but no one saw it all.' His close friend Charlie Bartlett, who had introduced him to Jackie, said, 'No one ever knew John Kennedy, not all of him.' Even Jackie threw up her hands, calling him 'a simple man, yet so complex that he would frustrate anyone trying to understand him,' concluding that 'to reveal yourself is difficult and almost dangerous' for people like the Kennedys. 'I'd say Jack didn't want to reveal himself at all.' One of the greatest challenges Kennedy poses to anyone writing about him is that, because he rigorously compartmentalized his friends and family members, their impressions and recollections of him are sometimes at odds. He was intellectually closer to Sorensen than to any other adviser, yet the two men did not socialize, and the president never invited Sorensen to the intimate dinners atthe White House family quarters (at which formerWashington Post editor Ben Bradlee was a frequent guest). Bradlee says he knew nothing about Kennedy's energetic philandering, yet Kennedy's trusted secretary Evelyn Lincoln knew about his womanizing and in at least one instance offered her home address so he could receive letters from a mistress there.

Three days before going to Dallas, he told Lincoln he was thinking of replacing Lyndon Johnson with North Carolina Gov. Terry Sanford as his running mate in 1964, but he did not share this bombshell with his brother Bobby, with whom he often spoke several times a day. Not surprisingly, Bobby later dismissed the conversation as a fabrication, telling historian Arthur Schlesinger, 'Can you imagine the president ever having a talk with Evelyn about a subject like that?' Yet when former Cabinet member Abe Ribicoff went sailing with Bobby several months after Dallas, he was shocked to discover that he knew things about John that Bobby did not, confirming his impression that the president had 'exposed different facets of himself to different people.' Despite these challenges, so much has been written about Kennedy, so many oral histories have been recorded about him and so many memoirs mention him that it is still possible to find things even devoted biographers didn't know.

In a 1986 set of recollections by close associates of Johnson, I found that, according to speechwriter and adviser Horace Busby, two weeks before JFK traveled to Texas, Johnson told Busby that when he was with the president in Austin on the evening of Nov. 22, he would tell him he had decided against running for vice president in 1964 and would instead return to Texas to run a newspaper. Busby doubted that he was serious and thought that LBJ just wanted the president to cajole and flatter him. But given Kennedy's increasing estrangement from Johnson, it is possible that he would have accepted his offer with alacrity.

In a seldom-read oral history in the Kennedy Library given by the Pulitzer Prize-winning author Margaret Coit, I came across her detailed description of Kennedy's unsuccessful attempt to seduce her in 1953. This led me to Coit's papers at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and to letters and diary entries containing a perceptive take on JFK's womanizing.

What struck Coit most was the effortless and machine-like way Kennedy shifted from the intellectual to the carnal, talking about books and ideas one minute and pawing her the next; behaving 'like a 14-year-old high school football player on the make,' and then 'like an elder statesman in his intellectual process.' The recent release of revealing new material has made an understanding of the multifaceted Kennedy more attainable. The publication of Sorensen's memoirs in 2008 and Jackie Kennedy's oral history in 2011 has shed new light on JFK's presidency and character, particularly on his deteriorating relationship with Johnson. Even more rewarding has been the release of the last of Kennedy's once-secret Oval Office tapes - as close as we are likely to get to the memoirs he never had a chance to write. Unlike Richard Nixon, Kennedy was a selective taper, activating his hidden recording system only when participating in a discussion he thought might merit inclusion in his memoirs.

Yet, even if there are no more great JFK revelations, biographers and historians will continue to be drawn to this elusive man because, as Kennedy once told his friend Bradlee, 'What makes journalism so fascinating and biography so interesting is the struggle to answer that single question: 'What's he like?' '

Thurston Clarke is the author of 'The Last Campaign: Robert F. Kennedy and 82 Days That Inspired America' and 'JFK's Last Hundred Days: The Transformation of a Man and the Emergence of a Great President.'

© 2013 Washington Post

Associated Press

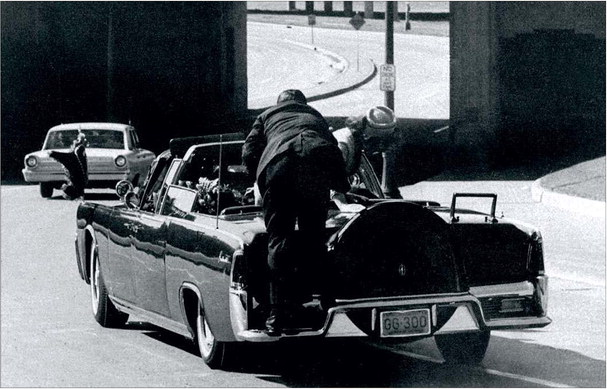

Fatally shot, President John F. Kennedy slumps down in the presidential limousine as it roars down the road. Jacqueline Kennedy leans over the president as Secret Service agent Clint Hill pushes her back to her seat. 'She's going to go flying off the back of the car,' Hill thought.