The Magic Bullet: Even

More Magical Than We Knew?

Gary Aguilar and Josiah Thompson

Introduction

|

Among the myriad JFK assassination controversies, none more

cleanly divides Warren Commission supporter from skeptic

than the “Single Bullet Theory.” The brainchild of a former

Warren Commission lawyer, Mr. Arlen Specter, now the senior

Senator from Pennsylvania, the theory is the sine qua non of

the Warren Commission’s case that with but three shots,

including one that missed, Lee Harvey Oswald had single

handedly altered the course of history. [Fig.

1] Mr. Specter’s hypothesis was not one that

immediately leapt to mind from the original evidence and the

circumstances of the shooting. It was, rather, born of

necessity, if one sees as a necessity the keeping of Oswald

standing alone in the dock. The theory had to contend with

the considerable evidence there was suggesting that more

than one shooter was involved.

For example, because the two victims in Dealey Plaza,

President Kennedy and Governor John Connally, had suffered

so many wounds – eight in all, it had originally seemed as

if more than two slugs from the supposed “sniper’s nest”

would have been necessary to explain all the damage. In

addition, a home movie taken by a bystander, Abraham

Zapruder, showed that too little time had elapsed between

the apparent shots that hit both men in the back for Oswald

to have fired, reacquired his target, and fired again. The

Single Bullet Theory neatly solved both problems. It posited

that a single, nearly whole bullet that was later recovered

had caused all seven of the non-fatal wounds sustained by

both men.[1] |

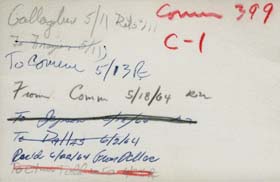

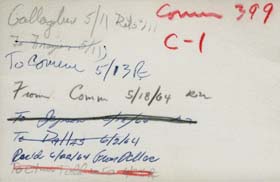

Figure 1. CE #399. Warren Commission Exhibit #399, said

to have caused both of JFK’s non-fatal wounds and all five

of the Governor Connally’s wounds, is shown in two views,

above left. Arlen Specter theorized the bullet had followed

a path much like the one shown at right. (National Archives

photo) |

But the bullet that was recovered had one strikingly peculiar

feature: it had survived all the damage it had apparently caused

virtually unscathed itself. The shell’s near-pristine appearance,

which prompted some to call it the “magic bullet,” left many

skeptics wondering whether the bullet in evidence had really done

what the Commission had said it had done. Additional skepticism was

generated by the fact the bullet was not found in or around either

victim. It was found instead on a stretcher at the hospital where

the victims were treated.

Mr. Specter’s idea was that, after passing completely through JFK

and Governor Connally, the bullet had fallen out of the Governor’s

clothes and onto a stretcher at Parkland Hospital. But it was never

unequivocally established that either victim had ever lain on the

stretcher where the bullet was discovered.[2]

Nevertheless, studies done at the FBI Laboratory seemed to

unquestionably link the missile to Oswald’s rifle, and the FBI sent

the Warren Commission a memo on July 7, 1964 detailing how it had

run down the bullet’s chain of possession, which looked pretty

solid. According to the FBI, the two hospital employees who

discovered the bullet originally identified it as the same bullet

six months later in an FBI interview

That a bullet, fired from Oswald’s weapon and later identified by

hospital witnesses, had immediately turned up on a stretcher in the

hospital where the victims were treated struck some as perhaps a

little too convenient. Suspicions it had been planted ensued. But

apart from its peculiar provenance, there was little reason in 1964

to doubt the bullet’s bona fides. But then in 1967, one of the

authors reported that one of the two hospital employees who had

found the bullet, Parkland personnel director O.P. Wright, had told

him that the bullet he saw and held on the day of the assassination

did not look like the bullet that later turned up in

FBI evidence. That claim was in direct conflict with an FBI memo of

July 7, 1964, which said that Wright had told an FBI agent that the

bullet did look like the shell he’d held on the day of

the murder.

For thirty years, the conflict lay undisturbed and unresolved.

Finally, in the mid 1990s, the authors brought this conflict to the

attention of the Assassinations Records Review Board, a federal body

charged with opening the abundant, still-secret files concerning the

Kennedy assassination. A search through newly declassified files led

to the discovery of new information on this question. It turns out

that the FBI’s own, once-secret files tend to undermine the position

the FBI took publicly in its July, 1964 memo to the Warren

Commission, and they tend to support co-author Josiah Thompson.

Thompson got a further boost when a retired FBI agent, in a recorded

telephone interview and in a face-to-face meeting, flatly denied

what the FBI had written about him to the Warren Commission in 1964.

A Bullet is Found at Parkland Hospital

The story begins in a ground floor elevator lobby at the Dallas

hospital where JFK and John Connelly were taken immediately after

being shot. According to the Warren Commission, Parkland Hospital

senior engineer, Mr. Darrell C. Tomlinson, was moving some wheeled

stretchers when he bumped a stretcher “against the wall and a bullet

rolled out.”[3]

He called for help and was joined by Mr. O.P. Wright, Parkland’s

personnel director. After examining the bullet together, Mr. Wright

passed it along to one of the U.S. Secret Service agents who were

prowling the hospital, Special Agent Richard Johnsen.[4]

|

Johnsen then carried the bullet back to Washington, D. C.

and handed it to James Rowley, the chief of the Secret

Service. Rowley, in turn, gave the bullet to FBI agent Elmer

Lee Todd,[5]

who carried it to agent Robert Frazier in the FBI’s Crime

Lab.[6]

Without exploring the fact that the HSCA discovered that

there may have been another witness who was apparently with

Tomlinson when the bullet was found, what concerns us here

is whether the bullet currently in evidence, Commission

Exhibit #399, is the same bullet Tomlinson found originally.

The early history of the bullet, Commission Exhibit #399,

is laid out in Warren Commission Exhibit #2011. This exhibit

consists of a 3-page, July 7, 1964 FBI letterhead memorandum

that was written to the Warren Commission in response to a

Commission request that the Bureau trace “various items of

physical evidence,” among them #399 [Fig.

2]. #2011 relates that, in chasing down the bullet’s

chain of possession, FBI agent Bardwell Odum took #399 to

Darrell Tomlinson and O.P. Wright on June 12, 1964. The memo

asserts that both men told Agent Odum that the bullet

“appears to be the same one” they found on the day of the

assassination, but that neither could “positively identify”

it. [Figs.

2,

3] |

Figure 2. C.E. 2011. Chain of possession of #399 (FBI

Letterhead Memo Dallas 7/7/64) |

Positive identification” of a piece of evidence by a witness

means that the witness is certain that an object later presented in

evidence is the same one that was originally found. The most common

way to establish positive identification is for a witness to place

his initials on a piece of evidence upon first finding it. The

presence of such initials is of great help later when investigators

try to prove a link through an unbroken chain of possession between

the object in evidence and a crime.

Understandably, neither Tomlinson nor Wright inscribed his

initials on the stretcher bullet. But that both witnesses told FBI

Agent Odum, so soon after the murder, that CE 399 looked like the

bullet they had found on a stretcher was compelling reason to

suppose that it was indeed the same one.

|

However, CE #2011 included other information that raised

questions about the bullet. As first noted by author Ray

Marcus,[7]

it also states that on June 24, 1964, FBI agent Todd, who

received the bullet from Rowley, the head of the Secret

Service, returned with presumably the same bullet to get

Secret Service agents Johnsen and Rowley to identify it.

#2011 reports that both Johnsen and Rowley advised Todd that

they “could not identify this bullet as the one” they saw on

the day of the assassination. # 2011 contains no comment

about the failure being merely one of not “positively

identifying” the shell that, otherwise, “appeared to be the

same” bullet they had originally handled. [Figs.

2,

3] Thus, in #2011 the FBI reported that both Tomlinson

and Wright said #399 resembled the Parkland bullet, but that

neither of the Secret Service Agents could identify it. FBI

Agent Todd originally received the bullet from Rowley on

11/22/63 and it was he who then returned on 6/24/64 with

supposedly the same bullet for Rowley and Johnsen to

identify. Given the importance of this case, one imagines

that by the time Todd returned, they would have had at least

a passing acquaintance. Had it truly been the same bullet,

one might have expected one or both agents to tell Todd it

looked like the same bullet, even if neither could

“positively identify” it by an inscribed initial. After all,

neither Tomlinson nor Wright had inscribed their initials on

the bullet, and yet #2011 says that they said they saw a

resemblance. |

Figure 3. Last two pages of 7/7/64 FBI memo to Warren

Commission, as published in C.E. #2011. Note that FBI states

that both Dallas witnesses said #399 looked like the bullet

they found on 11/22/63. |

And there the conflicted story sat, until one of the current

authors published a book in 1967.

Two Different Accounts from One Witness

|

Six Seconds in Dallas reported on an interview

with O.P. Wright in November 1966. Before any photos were

shown or he was asked for any description of #399, Wright

said: “That bullet had a pointed tip.” “Pointed tip?”

Thompson asked.

“Yeah, I’ll show you. It was like this one here,” he

said, reaching into his desk and pulling out the .30 caliber

bullet pictured in Six Seconds.”[8]

As Thompson described it in 1967, “I then showed him

photographs of CE’s 399, 572 (the two ballistics comparison

rounds from Oswald’s rifle) (sic), and 606 (revolver

bullets) (sic), and he rejected all of these as resembling

the bullet Tomlinson found on the stretcher. Half an hour

later in the presence of two witnesses, he once again

rejected the picture of 399 as resembling the bullet found

on the stretcher.”[9]

[Fig.

4] |

Figure 4. In an interview in 1966, Parkland Hospital

witness O.P. Wright told author Thompson that the bullet he

handled on 11/22/63 did not look like C.E. # 399. |

|

Thus in 1964 the Warren Commission, or rather the FBI,

claimed that Wright believed the original bullet resembled

#399. In 1967, Wright denied there was a resemblance. Recent

FBI releases prompted by the JFK Review Board support author

Thompson’s 1967 report. A declassified 6/20/64 FBI AIRTEL

memorandum from the FBI office in Dallas (“SAC, Dallas” –

i.e., Special Agent in Charge, Gordon Shanklin) to J. Edgar

Hoover contains the statement, “For information WFO (FBI

Washington Field Office), neither DARRELL C. TOMLINSON

[sic], who found bullet at Parkland Hospital, Dallas, nor O.

P. WRIGHT, Personnel Officer, Parkland Hospital, who

obtained bullet from TOMLINSON and gave to Special Service,

at Dallas 11/22/63, can identify bullet … .” [Fig. 5 -

Page 1,

Page 2]

Whereas the FBI had claimed in CE #2011 that Tomlinson

and Wright had told Agent Odum on June 12, 1964 that CE #399

“appears to be the same” bullet they found on the day of the

assassination, nowhere in this previously classified memo,

which was written before CE #2011, is there

any corroboration that either of the Parkland employees saw

a resemblance. Nor is FBI agent Odum’s name mentioned

anywhere in the once-secret file, whether in connection with

#399, or with Tomlinson or with Wright. |

Figure 5. Declassified FBI memo reporting neither Tomlinson

nor Wright could identify “C1” [#399] as the bullet they

handled on 11/22/63.

[Page

1,

Page 2] |

|

A declassified record, however, offers some

corroboration for what CE 2011 reported about Secret Service

Agents Johnsen and Rowley. A memo from the FBI’s Dallas

field office dated 6/24/64 reported that, “ON JUNE

TWENTYFOUR INSTANT RICHARD E. JOHNSEN, AND JAMES ROWLEY,

CHIEF … ADVISED SA ELMER LEE TODD, WFO, THAT THEY WERE

UNABLE TO INDENTIFY RIFLE BULLET C ONE (# 399, which, before

the Warren Commission had logged in as #399, was called “C

ONE”), BY INSPECTION (capitals in original). [Fig.

6] Convinced that we had overlooked some relevant

files, we cast about for additional corroboration of what

was in CE # 2011. There should, for example, have been some

original “302s ” – the raw FBI field reports from the Agent

Odum’s interviews with Tomlinson and Wright on June 12,

1964. There should also have been one from Agent Todd’s

interviews with Secret Service Agents Johnsen and Rowley on

June 24, 1964. Perhaps somewhere in those, we thought, we

would find Agent Odum reporting that Wright had detected a

resemblance between the bullets. And perhaps we’d also find

out whether Tomlinson, Wright, Johnsen or Rowley had

supplied the Bureau with any additional descriptive details

about the bullet. |

Figure 6. Suppressed 1964 FBI report detailing that

neither of the Secret Service agents who handled “#399” on

11/22/63 could later identify it. |

In early 1998, we asked a research associate, Ms. Cathy

Cunningham, to scour the National Archives for any additional files

that might shed light on this story. She looked but found none. We

contacted the JFK Review Board’s T. Jeremy Gunn for help. [Fig.

7] On May 18, 1998, the Review Board’s Eileen Sullivan, writing

on Gunn’s behalf, answered, saying: “[W]e have attempted,

unsuccessfully, to find any additional records that would account

for the problem you suggest.”[10]

[Fig.

8] Undaunted, one of us wrote the FBI directly, and was referred

to the National Archives, and so then wrote Mr. Steve Tilley at the

National Archives. [Fig.

9]

On Mr. Tilley’s behalf, Mr. Stuart Culy, an archivist at the

National Archives, made a search. On July 16, 1999, Mr. Culy wrote

that he searched for the FBI records within the HSCA files as well

as in the FBI records, all without success. He was able to

determine, however, that the serial numbers on the FBI documents ran

“concurrently, with no gaps, which indicated that no material is

missing from these files.”[11]

[Fig.

10] In other words, the earliest and apparently the only FBI

report said nothing about either Tomlinson or Wright seeing a

similarity between the bullet found at the hospital and the bullet

later in evidence, CE #399. Nor did agent Bardwell Odum’s name show

up in any of the files.

|

Figure 7. Letter to Assassinations Records Review Board

requesting a search for records that might support FBI’s

claim that hospital witnesses identified #399. |

Figure 8. ARRB reports that it is unable to find records

supporting FBI claim Parkland Hospital witnesses identified

#399. |

Figure 9. Letter to National Archives requesting search

for additional files on C.E. #399. |

Figure 10. Letter from National Archives disclosing no

additional files exist on C.E. #399. |

[editor's note: Dr. Aguilar followed up in 2005 with the National

Archives, asking them in letters dated

March 2 and

March 7 to search for any FBI "302" reports that would have been

generated from CE399 being shown to those who handled it. On

March 17, 2005 David Mengel of NARA wrote back reporting that

additional searches had not uncovered any such reports.]

Stymied, author Aguilar turned to his co-author. “What does Odum

have to say about it?” Thompson asked.

“Odum? How the hell do I know? Is he still alive?”

“I’ll find out,” he promised.

Less than an hour later, Thompson had located Mr. Bardwell Odum’s

home address and phone number. Aguilar phoned him on September 12,

2002. He was still alive and well and living in a suburb of Dallas.

The 82-year old was alert and quick-witted on the phone and he

regaled Aguilar with fond memories of his service in the Bureau.

Finally, the Kennedy case came up and Odum agreed to help interpret

some of the conflicts in the records. Two weeks after mailing Odum

the relevant files – CE # 2011, the three-page FBI memo dated July

7, 1964, and the “FBI AIRTEL” memo dated June 12, 1964, Aguilar

called him back.

|

Mr. Odum told Aguilar, “I didn’t show it [#399] to anybody

at Parkland. I didn’t have any bullet … I don’t think I ever

saw it even.” [Fig.

11] Unwilling to leave it at that, both authors paid Mr.

Odum a visit in his Dallas home on November 21, 2002. The

same alert, friendly man on the phone greeted us warmly and

led us to a comfortable family room. To ensure no

misunderstanding, we laid out before Mr. Odum all the

relevant documents and read aloud from them.

Again, Mr. Odum said that he had never had any bullet

related to the Kennedy assassination in his possession,

whether during the FBI’s investigation in 1964 or at any

other time. Asked whether he might have forgotten the

episode, Mr. Odum remarked that he doubted he would have

ever forgotten investigating so important a piece of

evidence. But even if he had done the work, and later

forgotten about it, he said he would certainly have turned

in a “302” report covering something that important. Odum’s

sensible comment had the ring of truth. For not only was

Odum’s name absent from the FBI’s once secret files, it was

also it difficult to imagine a motive for him to besmirch

the reputation of the agency he had worked for and admired. |

Figure 11. Recorded interview with FBI Agent Bardwell

Odum, in which he denies he ever had C.E. #399 in his

possession. |

Thus, the July 1964 FBI memo that became Commission Exhibit #2011

claims that Tomlinson and Wright said they saw a resemblance between

#399 and the bullet they picked up on the day JFK died. However, the

FBI agent who is supposed to have gotten that admission, Bardwell

Odum, and the Bureau’s own once-secret records, don’t back up #2011.

Those records say only that neither Tomlinson nor Wright was

able to identify the bullet in question, a comment that leaves the

impression they saw no resemblance. That impression is strengthened

by the fact that Wright told one of the authors in 1966 the bullets

were dissimilar. Thus, Thompson’s surprising discovery about Wright,

which might have been dismissed in favor of the earlier FBI evidence

in #2011, now finds at least some support in an even earlier,

suppressed FBI memo, and the living memory of a key, former FBI

agent provides further, indirect corroboration.

Missing 302s?

|

But the newly declassified FBI memos from June 1964 lead to

another unexplained mystery. Neither are the 302 reports

that would have been written by the agents who investigated

#399’s chain of possession in both Dallas and Washington.

The authors were tempted to wonder if the June memos were

but expedient fabrications, with absolutely no 302s

whatsoever backing them up. But a declassified routing

slip turned up by John Hunt seems to prove that the FBI did

in fact act on the Commission’s formal request, as outlined

in # 2011, to run down #399s chain of possession. The

routing slip discloses that the bullet was sent from

Washington to Dallas on 6/2/64 and returned to Washington on

6/22/64. Then on 6/24/64, it was checked out to FBI Agent

Todd. [Fig.

12] What transpired during these episodes? If the Bureau

went to these lengths, it seems quite likely that Bardwell

Odum, or some other agent in Dallas, would have submitted

one or more 302s on what was found, and so would Agent Elmer

Todd in Washington. But there are none in the files. The

trail ends here with an unexplained, and perhaps important,

gap left in the record. |

Figure 12. FBI routing slip. Note that #399 was sent

from Washington to Dallas and back again, and that FBI agent

Todd checked out the bullet on 6/24/64, the day it was

reported the Secret Service Agents told Todd they could not

identify #399. [See Fig. 5 (page

1,

page 2) and

Fig. 6.] (Courtesy of John Hunt) |

Besides this unexplained gap, another interesting question

remains: If the FBI did in fact adjust Tomlinson and Wright’s

testimonies with a bogus claim of bullet similarity, why didn’t it

also adjust Johnsen and Rowley’s? While it is unlikely a certain

answer to this question will ever be found, it is not unreasonable

to suppose that the FBI authors of #2011 would have been more

reluctant to embroider the official statements of the head of the

Secret Service in Washington than they would the comments of a

couple of hospital employees in Dallas.

Summary

In a memo to the Warren Commission [C. E. #2011] concerning its

investigation of the chain of possession of C.E. #399, the FBI

reported that two Parkland Hospital eyewitnesses, Darrell Tomlinson

and O. P. Wright, said C.E. #399 resembled the bullet they

discovered on the day JFK died. But the FBI agent who is supposed to

have interviewed both men and the Bureau’s own suppressed records

contradict the FBI’s public memo. Agent Odum denied his role, and

the FBI’s earliest, suppressed files say only that neither

Tomlinson nor Wright was able to identify the bullet in question.

This suppressed file implies the hospital witnesses saw no

resemblance, which is precisely what Wright told one of the authors

in 1967.

What we are left with is the FBI having reported a solid chain of

possession for #399 to the Warren Commission. But the links in the

FBI’s chain appear to be anything but solid. Bardwell Odum, one of

the key links, says he was never in the chain at all and the FBI’s

own, suppressed records tend to back him up. Inexplicably, the chain

also lacks other important links: FBI 302s, reports from the agents

in the field who, there is ample reason to suppose, did actually

trace #399 in Dallas and in Washington. Suppressed FBI records and

recent investigations thus suggest that not only is the FBI’s file

incomplete, but also that one of the authors may have been right

when he reported in 1967 that the bullet found in Dallas did not

look like a bullet that could have come from Oswald’s rifle.

[1] The eighth wound, JFK’s head wound, accounted for one of the

bullets. And evidence from the scene and from a home movie taken of

the murder by a bystander, Abraham Zapruder, suggests that a third

bullet had missed entirely.

[2] Josiah Thompson. Six Seconds in Dallas.

Bernard Geis Associates for Random House, 1967, p. 161 –

164.

[3] The President’s Commission on the Assassination of President

John F. Kennedy – Report. Washington, D.C.: U. S. Government

Printing Office, 1964,

p. 81. See also

6H130 – 131.

[4]

18H800. See also: Thompson, J. Six Seconds in Dallas.

New York: Bernard Geis Associates for Random House,

1967, p. 155.

[5]

24H412.

[6]

3H428;

24H412.

[7] See Ray Marcus monograph, The Bastard Bullet.

[8] Text of email message from Josiah Thompson to Aguilar,

12/10/99.

[9] Thompson, Josiah. Six Seconds in Dallas. New

York: Bernard Geis Associates for Random House,

1967, p. 175.

[10] 5/11/98 email message from Eileen Sullivan re: “Your letter

to Jeremy Gunn, April 4, 1998.”

[11] Personal letter from Stuart Culy, archivist, National

Archives, July 16, 1999. |