Angel is Airborne

Aboard

Air Force One—during one of

America

’s most searing, perilous moments—a government was formed and a presidency

begun.

Part

II: In the Air

CHAPTER 8

The

world had barely kept up with Lyndon Johnson in the turmoil following the

shooting. For nearly an hour after Walter Cronkite announced on CBS that Kennedy

was dead, the public had no idea where Johnson was. Reporters heard only that he

would take the oath of office at Love Field at 2:35 pm, just three minutes

before Judge Hughes swore him in. By the time word spread that Johnson had taken

the oath officially as President, Air Force One was already flying back to

Washington—the country’s new chief executive out of reach and out of sight

for two seemingly interminable hours.

President

John F. Kennedy's pilot, Col. James B. Swindal, and co-pilot Maj. Lewis

"Swede" Hanson, check Air Force One's cockpit before take-off at

Andrews Air Force Base on May 13, 1963. (AP Photo/John Rous)

Nor

did anyone on earth know who was and was not aboard Air Force One. No list had

been left behind in

At

one point, well after Air Force One’s departure from

“Air

Force One—this is the Air Force Command Post,” the radio squawked. “If

possible, request the names of the passengers onboard, please.”

“We

have 40-plus,” the plane responded.

“Forty

people! Is that affirmative?”

“Affirmative.”

“Can

you tell me in regard to number one and number two—the top people?”

“Roger,”

Air Force One explained. “The President is onboard. The body is onboard, and

Mrs. Kennedy is onboard.”

Never

before or since has Air Force One carried two Presidents at once—one dead, one

alive. Never before or since has a Vice President witnessed the murder of his

President. Never before or since in the nuclear age has an assassination forced

the government into a panicked transition from one chief executive to another.

And never before or since have the aides of the fallen President and the

incoming President been locked together for hours in an aluminum tube, with one

another and their own thoughts.

In

fact, we may never know precisely how many people were aboard Air Force One as

it took off for

Scrawled

at the bottom of the page by a hand obviously unsure where to place such a

tragic piece of information are words that make a reader pause: “Also body of

Pres. K—.”

Normally

there would have been as many as a dozen Air Force staff on the plane, including

the three-person cockpit crew—the pilot, copilot, and flight

engineer—stewards, and a baggage master as well as members of the White House

Communications Agency, responsible for the plane’s communications.

The

Secret Service’s official manifest, recreated in February 1964 by Roy

Kellerman, one of the agents aboard, lists the 13 crew members the Secret

Service believes were onboard “for the entire trip to

Two

of JFK’s press aides, Christine Camp and Sue Vogelsinger, were hurriedly

removed from the plane moments before takeoff and so figure into some accounts

of the plane’s flight even though they weren’t onboard at departure, and

William Manchester’s book The Death of a President erroneously

identifies as a passenger Marty Underwood, a Democratic advance man, who

actually returned to DC on Air Force Two.

While

the country wrestled with the news of Kennedy’s assassination and the hunt for

his killer unfolded, that odd assortment of friends, rivals, and strangers who

had assembled at Love Field found themselves pressed together under the most

intense circumstances, eight miles above their devastated nation, dodging storm

clouds at nearly 600 miles per hour as they raced home.

CHAPTER 9

Much

has been made in political mythology of the slights, factions, and egos present

on the Boeing 707 that afternoon, how the Johnson people pushed aside the

Kennedy men, disrespecting the widow even as her husband’s blood dried into

her Chanel-inspired suit. But a comprehensive examination of the day’s flight

reads less like a Machiavellian case study than an intensely human story of four

dozen people—most of them shell-shocked, afraid, and confused—and their

desperate push to figure out what had happened and how America would continue

on.

The

Boeing 707 that served as Kennedy's presidential plane, SAM 26000, was the first

jet aircraft to serve the commander-in-chief. Jackie Kennedy had famed

industrial designer Raymond Loewy redo the plane's markings and his paint scheme

is what it still used today on Air Force One. (U.S. Air Force photo)

They

had two hours and 12 minutes together to mourn their fallen leader and create a

new government. Inside the 153-foot-long fuselage, with little privacy and

limited communication with the outside world, loyalties evolved and careers

began—and ended. Before the plane had even left the ground, that sorting-out

began: Godfrey McHugh’s distinguished military career would never recover from

his grief-stricken “I have only one President” comment made to Malcolm

Kilduff. Within days, McHugh would be among the first staff cut from the Johnson

White House.

Now,

as the clock passed 3pm CST (4pm in Washington) and the jet soared ever

higher—pilot James Swindal finally leveled off at 41,000 feet, near the very

edge of the 707’s performance—the bright-blue Texas sky quickly gave way to

the darker blues of twilight. The pilots plotted their path home, making contact

with air-traffic controllers below:

But

in the sky, they were alone above the earth, flying without a net. Every 15

minutes, as it burned fuel at a rate of a gallon a second and the plane’s

weight lessened, Swindal or copilot Lewis Hanson reduced the plane’s throttles

to maintain its maximum speed of Mach .84. In its nearly 30 years of

presidential service, the aircraft—tail number SAM 26000—would never fly

higher or faster than it did that day.

For

the first few minutes after takeoff, nearly everyone sat silently. The cabin

began to cool down once it was airborne and the air conditioning was cranked up.

The Johnsons sat in the forward compartment with the three

The

military and Secret Service agents theoretically treated every President the

same. Yet McHugh, Swindal, and other military men found to their surprise that

Kennedy had meant something special to them—and that loyalty wasn’t

painlessly transferred to this new Texan. Meanwhile, Kilduff—already elbowed

aside by the Kennedy men and now pressed into service—moved quickly to

Johnson’s side, where he would remain for the next two years.

The

November sun set quickly as the plane moved east, but a different darkness

settled in the cockpit. “Suddenly realizing that President Kennedy was dead, I

felt that the world had ended and it became a struggle to continue,” Air Force

One pilot Swindal wrote later. “I know that I personally will never again

enjoy flying as I did before.”

CHAPTER 10

It

wouldn’t be easy to create a government nearly alone eight miles above the

earth in a span of time roughly equal to that of a Friday-night movie. Normally,

Presidents have months between being elected and assuming office to plan

transitions, interview staff, and establish policy.

In

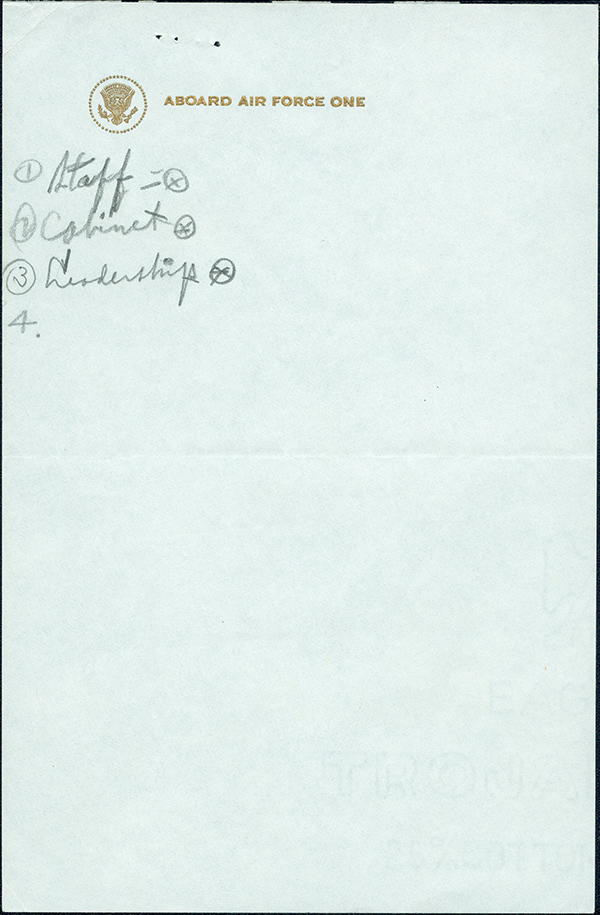

the forward cabin after takeoff, Lyndon Johnson grabbed a piece of blue

notepaper, printed with the presidential seal and gold letters reading aboard

air force one, and wrote a numbered list, 1 through 4:

Johnson's

to-do list in the first hours of his presidency, jotted down quickly on Air

Force One, left much unsaid. (LBJ Presidential Library)

1)

Staff

2)

Cabinet

3)

Leadership

4)

That

last line sat empty, pregnant with all that he had to do.

And

so the machinery of governance began to turn. He summoned Bill Moyers to help

assign tasks. Then Johnson started working the phones, seeking out anyone who

could help.

Technology

limited communications with Air Force One. Although nine phone extensions were

onboard, only three simultaneous conversations could take place with people one

the ground. The top-of-the-line radiophone in the new Boeing 707 was a huge

upgrade to Air Force One’s telecommunications system, but it still was hard to

hold a conversation for long. “As we became airborne, I did not know what to

expect,” the signalman and radio operator, Sergeant John Trimble, later

recalled. “However, since they had to go through me, I knew that I was in for

one hell of a ride.”

Trimble

was busy every minute of the flight. “Andrews always had a waiting list of

various officials who wanted to communicate with the plane,” he said. “Many

times I had to decide with whom we would talk next.”

Each

phone call was a struggle, the communications channel full of static and with a

significant transmission lag. A typical conversation required lots of repeating

and confirming that the other party had actually understood the transmission.

“You

get that, operator?”

“Air

Force One, Andrews. Say again, please.”

“.

. . Helicopter . . . .”

“You

getting that?”

“Negative.”

“Let’s

try them again.”

As

Trimble summed up: “People talking to and from Air Force One on November 22

showed a great amount of patience.”

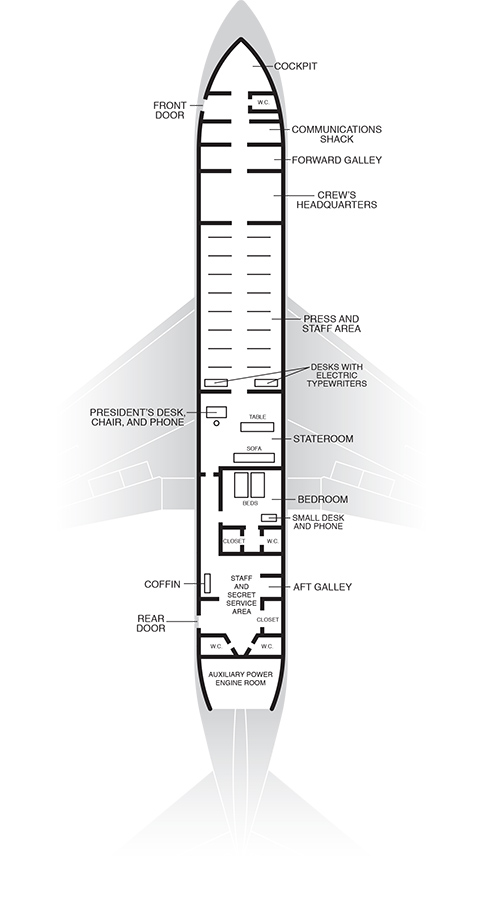

This

schematic shows the layout of Air Force One as it was on November 22, 1963.

The

new President’s calls, though, always took precedence. In stark contrast to

later claims that Johnson had grabbed for power, one of his first orders of

business was to reach out to the wounded.

Air

Force One was somewhere over

“Yes,

Mr. President?” she said, formally—addressing the man with the title that

until two hours earlier had belonged to her son.

“Mrs.

Kennedy, I wish to God that there was something I could say to you, and I want

to tell you that we’re grieving with you,” he said.

“Thank

you very much. That’s very nice. I know you loved Jack and he loved you,”

she replied warmly but formally.

“If

there is anything we can do—” Lady Bird began. Then the two women’s words

tripped over each other.

“Thank

you, Lady Bird. Thank you, Mr. President,” Mrs. Kennedy said, ending the call.

The

couple’s next call was back to

“Can

you hear me?” Lady Bird asked Nellie Connally. “The surgeon speaking about

John was so reassuring. How about it?”

“The

surgeon that just finished operating said that John is going to be all right

unless something unforeseen happens,” Mrs. Connally reported.

“I

know that everything’s going to be all right,” said LBJ, who in fact knew no

such thing.

“Yes,

everything’s going to be all right,” Lady Bird added.

“Good

luck,” Mrs. Connally wished the new First Couple.

As

the President worked his way through his calls, inbound messages stacked up.

Four times, Tazewell Shepard, Kennedy’s naval aide back at the White House,

tried unsuccessfully to reach Air Force One. And the White House communications

team tried several times to put through a condolence message from Queen

Elizabeth. They finally passed it along—in addition to three or four other

calls from heads of state—to General Clifton’s aide to give LBJ when he

arrived at the White House later that night.

Not

all of the radio traffic, though, involved the President or covered matters of

the highest urgency. Congressman Thomas, for instance, realized that no one was

expecting him in Washington—he had been scheduled to stay in Texas a few days

longer—and needed a favor from his staff.

“I

need Capital 4-3121 extension 493,” Trimble radioed to the White House.

“I’ll talk to anyone there.”

“Say

again?” the White House switchboard replied. “It was Capital 4-3291

extension 493?”

“That’s

4-3121 extension 493.”

“Roger,

roger. Understand. Anyone in particular there?”

“Roger.

Anyone at that number.”

“Roger.

Stand by.” Long pause. “Air Force One, Air Force One from Crown. Was that

extension 493?”

“That

is affirmative. Congressman Thomas’s office.”

“Say

again the congressman’s name, as they say they have no such extension.”

“Congressman

Thomas. Tango—Hotel—Oscar—Mike—Alpha—Sierra . . . .”

“Roger,

roger, stand by,” the White House finally reported back. “Congressman

Thomas’s office on the line.”

“Roger.

This is the airplane. The congressman is requesting that you place his door keys

under the doormat of his residence. Go ahead.”

“Oh,

okay. Hello?” a confused female congressional aide replied.

“Hello,

did you hear me?”

“There

will be someone at his residence,” the aide said.

“I

understand the house will be open. And someone will be in the residence. Is that

correct?” the Air Force One signalman radioed. “Hello? I understand that the

house will be occupied. That someone will be home. Is that right?”

Finally

the White House chimed back in: “Air Force One, this is Crown, that is a

Roger. She said that there will be someone at the residence.”

“Okay.

Fine, Crown. Thank you very much,” Air Force One concluded the call.

Congressman

Thomas wouldn’t be without clean clothes.

Between

phone calls, the Air Force weather station kept the flight crew informed about

tornados around

CHAPTER 11

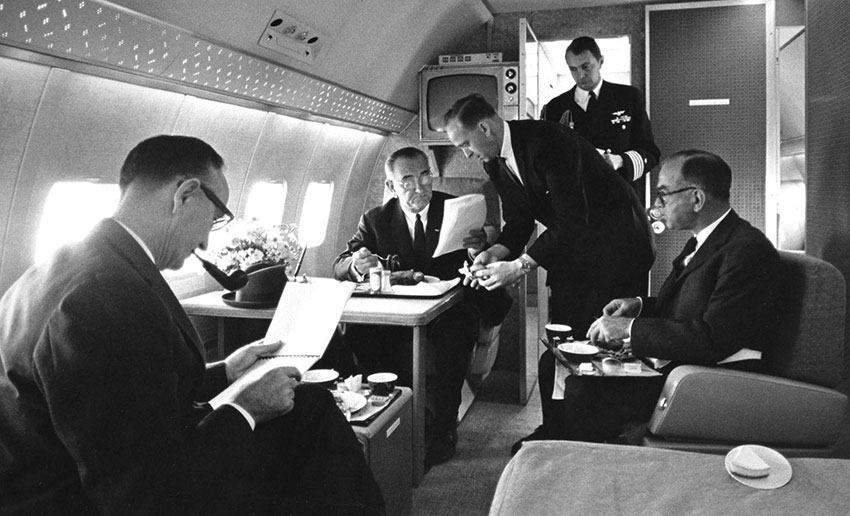

Johnson

plopped into one of the chairs in the stateroom and gathered Bill Moyers, Jack

Valenti, and Liz Carpenter around him. “I want you to put something down for

me to say when we land at Andrews,” he said as he sipped a glass of water.

“Nothing long. Make it brief. We’ll have plenty of time later to say

more.” During the short conversation, Valenti’s eyes were drawn to the

President’s large hands—they were absolutely steady. Valenti didn’t

understand how someone under such immense and immediate pressure could ever be

so collected. “I want to make clear that the presidency will go on,” Johnson

said.

The

three set to their own drafts, which Johnson then began to edit himself.

Normally a regular drinker, he didn’t touch any alcohol on the flight; instead

he sipped Sanka nearly the entire time.

Johnson,

shown here in Air Force One's presidential bedroom on a later flight, was

immediately uncomfortable in the room when he arrived on the plane November 22,

1963. Serving LBJ is Chief Master Sergeant Paul Glynn, Johnson's Air Force

valet. (U.S. Air Force photo)

Meanwhile,

Marie Fehmer busily took dictation from passengers as they recounted the day’s

events, each of them trying to piece together more than just snapshots of

trauma. Congressman Brooks remembered hearing the three shots. Johnson aide

Cliff Carter recalled Ken O’Donnell entering the room at

The

plane’s arrival at Andrews preoccupied LBJ. Even as aides cautioned that Air

Force One’s landing should be conducted secretly, Johnson wanted a standard

press arrival. It mustn’t, he said, “look like we’re in a panic.” Everything must be normal.

“It’s

the Kremlin that worries me,” Johnson said later, sitting at the stateroom

desk. “It can’t be allowed to detect a waver.” He had seen Kennedy

humiliated at the Vienna Summit early in his own presidency; he couldn’t show

the same weakness. “Khrushchev is asking himself right now what kind of man I

am. He’s got to know he’s dealing with a man of determination.”

Johnson,

after all, was a

man of determination. Once the Senate majority leader and among the most

powerful people in

He

had been a good soldier, fiercely loyal to Kennedy, all anyone could ask of a

Vice President. Yet there had already been talk that Johnson might be dumped

from the ’64 ticket.

Just

that fall, the TV show Candid Camera had used the Vice President’s increasing

obscurity to comedic effect, asking random people: “Who is Lyndon Johnson?”

Everyone demurred; one man suggested the questioner look in a phone book.

Just

that fall, the TV show Candid Camera had

used the Vice President’s increasing obscurity to comedic effect, asking

random people: “Who is Lyndon Johnson?” Everyone demurred; one man suggested

the questioner look in a phone book. Others guessed a baseball player or an

astronaut. No one correctly identified the man who was now leader of the free

world, the man who had suddenly after three rifle shots assumed control of the

largest weapons arsenal in the history of the planet, the man now huddled in the

sitting room of Air Force One with just two hours until he had to introduce

himself to the world and reassure a devastated nation.

Before

Now

he was king. For as John Adams had said, there was but one piece of magic in the

otherwise most worthless job in

Johnson

had wanted to be President more than anything.

But

he hadn’t wanted it like this. Not with his leader’s murder. Not even Lyndon

Johnson was that hungry for power.

Now

he and his wife were entering a new world. Lady Bird had never even seen the

inside of Air Force One before boarding it to fly back to

It

was an instant transition and transformation difficult for nearly anybody in the

country to grasp, especially the four dozen people on Air Force One who had lost

a friend, a boss, and a commander. Yet even far removed from their leader and

the situation on that plane, the nation ground to a stop as word of Kennedy’s

assassination spread.

In

JFK’s

murder stunned the world like few other events in modern times. Sir Laurence

Olivier stopped a performance at

As

presidential historian Henry Graff put it later: “Lyndon Johnson’s ascent to

the presidency came at the most traumatic moment in American political

history.”

CHAPTER 12

Charles

Roberts and Merriman Smith, the two reporters aboard the plane, worked

frantically to write their stories using scrounged supplies and borrowed

typewriters. Aides and officials stopped by their workspace to whisper details

or offer memories of the day. Brigadier General McHugh made one trip forward to

remind them that he’d otherwise stood guard by the casket throughout the

journey. Mac Kilduff passed along decisions as the staff made them, and

President Johnson himself stopped by the newsmen’s table at one point to

explain that he intended to ask the Kennedy Cabinet to stay on.

“We

had so darn much work,” Newsweek’s Roberts

said later. “This was the only time in my life that I ever felt like saying to

a President of the

In

the main staff cabin, Roberts tried to ask Roy Kellerman some details of the

shooting but couldn’t bring himself to interrogate the Secret Service agent

for long. “His eyes were brimming,” Roberts later said, and Kellerman was

far from alone: Many “strong men [were] crying on the plane that day,”

Roberts recalled.

Next

to Roberts, Merriman Smith—the mustachioed 50-year-old UPI wire correspondent

known to everyone as “Smitty”—was trying to hide his inner turmoil as the

day’s events unfolded. He had broken the news of JFK’s shooting—the 15

bells that had rung in every newsroom in the country alerting editors to his

urgent FLASH from the motorcade press car: “Dallas, Nov. 22 (UPI)—THREE

SHOTS WERE FIRED AT PRESIDENT KENNEDY’S MOTORCADE IN DOWNTOWN DALLAS.

JT1234PCS—”

The

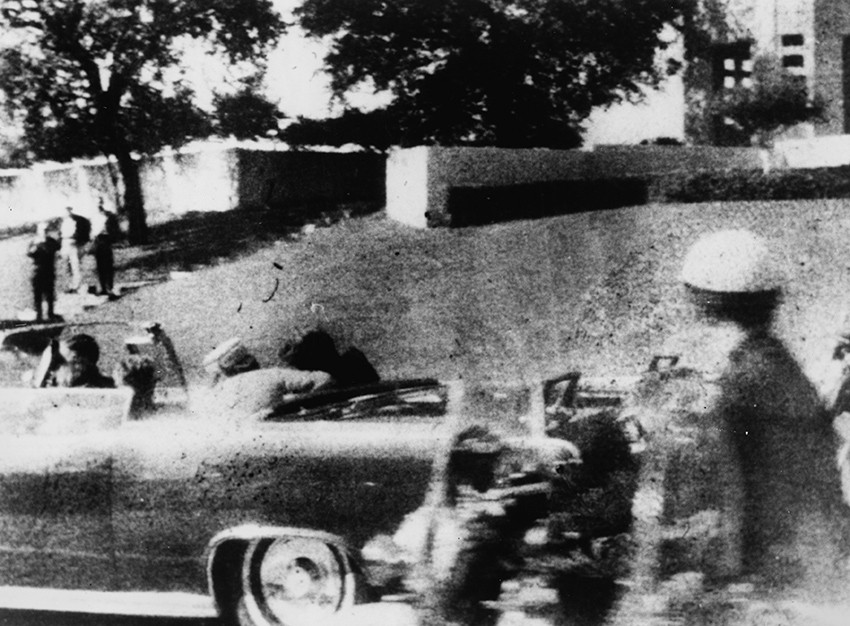

work that day of Merriman Smith, one of the two journalists aboard Air Force

One, would earn him the Pulitzer Prize. (Photo by Mary Moorman/Wikimedia

Commons)

Then

just five minutes later: “FLASH FLASH KENNEDY SERIOUSLY WOUNDED PERHAPS

SERIOUSLY PERHAPS FATALLY BY ASSASSINS BULLET JT1239PCS.” Then more.

Within

11 minutes of the shooting, Smith had dictated a 500-word story. He’d been

feeding updates to UPI about the President’s death when Secret Service agent

Rufus Youngblood stopped him in the

The

reporter’s work that day would earn him a Pulitzer Prize. Sadly, this flight

was now his second trip back to

“In

JFK’s death,” he wrote in his diary a year later, “my sense of loss had

taken the form of simply being unable to accept in my guts the coarse image and

patois of LBJ.”

At

times, it was as if there were two entirely different plane trips in progress.

The

front of the aircraft was a hive of activity—Johnson aides and military and

press officials scrambling for free radio time, workspace, and typewriters as

they tried to report, assemble, and organize a government from miles above the

earth. The rear, though, often seemed like the tomb it was, or an airborne Irish

wake.

The

trio of Kennedy aides whom the President had always jokingly called “the

clowns”—O’Donnell, Powers, and O’Brien—joined Jackie there. There was

little additional room in the aft compartment, so the other Kennedy aides were

left to visit one at a time: Jackie’s press aide, Pamela Turnure; JFK

secretary Evelyn Lincoln; and Secret Service agent Clint Hill. As they flew

north, O’Donnell encouraged Jackie to have a Scotch. “I’m going to have a

hell of a stiff drink,” he said. “I think you should, too.”

“I’ve

never had Scotch in my life,” she replied, then paused. “Now is as good a

time to start as any.”

But

she barely touched the whisky. (Jackie drank only Scotch in the months ahead.

She never once liked it, but it reminded her of the pain of that flight—a pain

she didn’t want to forget.) The aides, though, took to the bottle with

abandon.

Seated

around a small table, one of the only things in the space not removed to fit the

casket, they drank and drank. “It was like drinking water,” O’Donnell

recalled. “It left us cold sober.”

Their

drinking, though, made an impression on the new President, and not a favorable

one. “I thought they were just wineheads,” Johnson said in a 1969 interview.

“They were just drinkers, just one drink after another coming to them trying

to drown out their sorrows. It was a peculiar situation that they sat back in

the back and never would come and join us.”

LBJ

asked O’Donnell three times to come forward to speak with him, but the Kennedy

aide refused to budge. “I sat with her the entire trip,” he said of Jackie

Kennedy. “She just wanted to talk. She talked the entire way.” They

reminisced about the President, about the family, about the Kennedy family home

in

“You

were with him at the start, and you’re with him at the end,” Jackie said to

Powers and the others.

She

was also already doing her own thinking.

The

former First Lady was so far from her two children, so eager to be

home—wherever home would now be after she moved out of the residence that she,

her husband, and their children had known for the last two years. In some ways,

she and JFK had never been closer than at the moment of his death.

Their

marriage had strengthened and blossomed in the preceding months, the loss of

newborn baby Patrick in August—their second child to die, after Arabella was

stillborn in 1956—having brought the couple closer together. She had been

gearing up for the campaign;

The

couple hadn’t even slept together the night before; the hard mattress the

President brought along on road trips was big enough for only one. She had slept

in the other bedroom of their three-room hotel suite. “You were great

today,” he had said before they went their separate ways at bedtime.

Yet

she was holding it together—barely.

“That

frail girl was close to composure, bringing to the surface some strength within

her while we three slobs dissolved,” O’Brien said later.

Jackie

began to plan. She remembered how her husband had loved Luigi Vena’s singing

and decided that the Italian tenor should sing “Ave Maria” at the funeral.

Next she determined that Cardinal Richard Cushing, the archbishop of

Dave

Powers and Ken O’Donnell recalled visiting the grave of the couple’s

deceased son, Patrick, the previous month in

“I’ll

bring them together now,” Jackie said, the plans already forming in her mind.

Her husband would be buried at

Conversations

were halting; starting, stopping, and then restarting, overlapping. Evelyn

Lincoln, at a loss for words, said, “Everything’s going to be all right.”

Jackie

just looked at her: “Oh, Mrs. Lincoln.”

Throughout

the flight, no one touched what Jackie called “that long, long coffin.” Mary

Gallagher resisted leaning over to kiss it. The others around her—O’Brien,

O’Donnell, and Powers—sat vigil, many of them lost in their own thoughts, of

both remembrance and guilt: O’Donnell, speaking to the Secret Service that

morning, had given the order to leave the armored bubble top off the

presidential limo. (“Politics and protection don’t mix,” he had told the

White House security chief, Jerry Behn, during one argument.)

At

one point, Jackie Kennedy mused openly that her husband had been martyred like

Abraham Lincoln. It was a theme the Kennedy people returned to again and again

as their conversations—half wake, half plans—unfurled like the fields

passing far below.

Jackie

already worried about her husband’s legacy. He had been such a student of

history. What would history now say about him? Not knowing that mere feet from

her the UPI reporter was grieving deeply for her husband—holding LBJ’s

accidental presidency against him even in its first hours—she worried about

how the emotion-prone journalist would record the day: What is history going to see in this except what Merriman Smith

wrote, that bitter man.

CHAPTER 13

When

the two camps collided, emotions—anger, fear, grief, often

interconnected—ran high.

“Why

don’t you get back and serve your new boss?” O’Donnell barked at General

Clifton at one point when the intelligence aide came to the rear to ask a

question.

“What’s

eating him? I’m just doing my job,”

Chief

Master Sergeant Joe Chappell, who was the flight engineer on Air Force One when

Kennedy was assassinated in

“To

be the confidant and trusted emissary of the President, and now, by a freakish,

ghoulish act of assassination to be isolated, alone, adrift, with the captain

missing and a new helmsman in charge, this abrupt transition could not be

handled by mere mortals,” Jack Valenti wrote later. “I didn’t see

hostility. All I saw was grief—bitter, dry-teared grief.”

O’Donnell

concurred: “Whatever resentment some of us might have felt, neither Dave

[Powers] nor I remember any open display of antagonism against Johnson.”

Up

front, Kilduff drank gin-and-tonics. He later estimated that he downed

two-thirds of a bottle of gin while single-handedly juggling the duties of an

entire press office.

“I

needed that White House staff,” Johnson said later. “Without them I would

have lost my link to John Kennedy, and without that I would have had no chance

of gaining the support of the media or the Eastern intellectuals. And without

that support I would have had absolutely no chance of governing the country.”

But

he also knew he needed to be patient. Toward the end of the flight, Johnson

canceled the staff meeting he had planned upon returning to

“All

of us tried to comfort them in a quiet way, but they were still dazed from the

whole thing,” Johnson aide Liz Carpenter explained. When Moyers went back at

one point to ask for O’Donnell’s help on a matter, O’Donnell looked at him

blankly: “Bill, I don’t have the stomach for it.”

And

that was that. That night in

General

Ted Clifton called national-security adviser McGeorge Bundy to plan for the

President’s arrival. “Two meetings tonight—[Secretary of Defense Robert]

McNamara and Bundy and the leadership about 7:30,”

“Does

he mean the Democratic leadership only?” Bundy asked.

“Bipartisan

leadership, and I’ll give you some names,”

Bundy—who

referred to Johnson as “the Vice President” throughout the conversation out

of habit—suggested that because the Cabinet Room was being rearranged and

might not be ready in time, they should plan to meet with the congressional

leadership in the Oval Office. But

“He

does not want to go into the mansion or in the Oval Room or the President’s

Office or the President’s Study. So if the Cabinet Room isn’t ready, then

put it in the Fish Room,”

“All

right, I will,” Bundy said.

Given

how carefully LBJ, even in the midst of a national crisis, orchestrated the

power shift to lessen the pain of the Kennedy camp, he was stung by the

accusations voiced four years later in William Manchester’s book that Johnson

had brazenly seized the crown, shoving aside the grieving Kennedy team. “I did

everything I could to show respect and affection and grief to Mrs. Kennedy,”

LBJ said later. “I don’t know of any niceties that were overlooked at all,

and what’s more, I think everybody in the party will say that.”

CHAPTER 14

On

the flight, the Secret Service pushed their new President to spend the night in

the White House. It was safe there, they knew, and Rufus Youngblood urged him

“to think of security first.”

But

Johnson cut off the conversation: “We are going home to The Elms. That’s

where we live. If you can protect us at the White House, by God you can protect

us at home, too.” He did not want to seem presumptuous.

Because

the Vice President of the United States didn’t have an official residence at

that time—and wouldn’t until a house on the grounds of the Naval Observatory

was designated as such in 1974—Johnson had commuted in to the White House each

day from the Spring Valley neighborhood. (His home at

His

orders clear, Youngblood squeezed himself into the plane’s communications

shack to call the White House security chief. The connection, again, was patchy

at best—beset with static and garbled transmissions and packed with code

names.

What

are commonly known as “Secret Service code names” are actually designations

given by the White House communications agency to officials and their families

and are grouped around the same letters: All the Kennedy family names began with

L: Lancer for JFK, Lace for Jackie, Lyric for Caroline, and Lark for John Jr.

The Johnson family had received V names: Volunteer for

“I

committed about 50 to memory and instructed others to use their last name,”

radioman Trimble recalled later. Then there were separate code names for major

destinations: Crown was the White House, Valley the Vice President’s residence

at The Elms. “Originally, the code names were a good idea and did facilitate

communications, but like most everything else in government, [they’ve] gotten

out of hand,” Trimble recalled. It was a lot to keep straight in a

conversation.

“Volunteer

will reside at Valley for an indefinite time,” Youngblood transmitted. “I

repeat: Volunteer will reside at Valley for an indefinite time.

“Will

you say again?” Jerry Behn asked from the White House. “Will you say

again?”

“Venus

should go out to Valley with agent,” a White House operator, also on the line,

tried to clarify.

“That

is a roger,” Youngblood said, sounding very far away from his colleagues at

just the moment they needed to be working closely together. “That is a roger.

Venus will go to Valley with agent.

“

“Okay,

that’s affirmative,” Behn said, but Youngblood still wasn’t sure the White

House had actually heard the main piece of information he was trying to convey:

The Secret Service had only a few hours to be ready for the President of the

United States to live outside the White House indefinitely for the first time

since Harry Truman had moved to Blair House during a post–World War II

renovation.

“Do

you also understand that for residential purposes Volunteer will reside at

Valley?” he asked.

“That

is affirmative,” Behn said, understanding. There was another short pause

before Behn repeated for emphasis, “That is affirmative.”

Youngblood

signed off: “All right—that is all the traffic I have at present.”

A

few minutes passed, and then a further thought from Air Force One. The plane

called back to the White House: Now that Johnson was President, the public

telephone line at his house—the one that was in the phone book—should be

disconnected and new, secure phones installed.

The

tarmac at Andrews Air Force One would be the first time Johnson presented

himself to the world as President of the

LBJ

also talked to McGeorge Bundy directly throughout the flight, attending to what

seemed to be a growing list of matters of state. Johnson was hungry for details

of the unfolding assassination investigation. Half an hour after takeoff, word

had come that a

American

military commanders around the world were moving their forces to a higher state

of readiness, but neither Bundy nor Johnson advocated a general alert or a move

to a higher so-called DEFCON.

Kilduff

and Valenti made several trips to the rear of the plane to ask if anyone needed

anything. The Kennedy men and Jackie barely acknowledged them. At one point, she

looked at Clint Hill—the Secret Service agent whom she had helped clamber onto

the trunk of the presidential limousine as it began to speed from the shooting

scene—and asked, “What will happen to you now?”

Around

5 pm, Admiral George Burkley, Kennedy’s physician, spoke with the Secret

Service and the military aides, realizing that one of the hardest conversations

of the trip fell to him. He passed through the President’s sitting room and

entered the silent, hallowed rear compartment to kneel next to the widow, her

Scotch before her on the table. He explained that her husband would have to be

autopsied.

“Why?”

“The

doctors must remove the bullet—the authorities must know the type. It becomes

evidence.”

“Well,

it doesn’t have to be done,” she said.

“Yes,

it is mandatory that we have an autopsy,” explained the admiral, who had

served as Kennedy’s doctor since the second month of his administration. “I

can do it at the Army hospital at Walter Reed or at the Navy hospital at

Burkley

hoped he could arrange it at a military hospital—the commander in chief

deserved that, and it would be the most secure facility possible. But in that

moment he was willing to indulge almost anything Jackie wanted. She thought for

a minute and then chose

General

McHugh later knelt beside her and asked again if she’d like to change clothes

before landing. She said what she’d said in

Someone

else suggested that Jackie could deplane on the right side of the aircraft, away

from the press and the television lights.

“We

will go out the regular way,” she said.

Ted

Clifton volunteered that an Army honor guard would be ready to carry the

President off the plane, but Jackie stopped him: “I want his friends to carry

him down.”

She

summoned Roy Kellerman, the head of JFK’s detail, and Dave Powers explained

that the Secret Service agents who were with the President would bear him off

the plane. Mrs. Kennedy wanted Bill Greer, his driver, to drive the ambulance.

Greer, who had spent the plane ride replaying in his mind the turn onto

General

Chester Clifton was known to most of his friends as Ted, but for official

purposes he was code-named Watchman. After Kellerman had arranged for the

autopsy,

“This

is Watchman,” he radioed Behn, the White House security chief. “I understand

that you have arranged for an ambulance to take President Kennedy to

“It

has been arranged to helicopter the body to

“Okay,

if it isn’t too dark. What about the First Lady?”

“Everyone

else will be helicoptered into the South Grounds.”

“Are

you sure that the helicopter operation will work? We have a very heavy

casket.”

“According

to Witness [naval aide Tazewell Shepard], yes.”

“Don’t

take a chance on that,”

“Affirmative.”

“Now

some other instruction. Listen carefully: We need a ramp put at the front of the

aircraft on the right-hand side just behind the pilot’s cabin in the galley.

We are going to take the First Lady off by that route.”

“Understand.”

“Also,

at the left rear—at the rear of the aircraft where we usually dismount, we may

need a forklift rather than a ramp. A platform to walk out on and a forklift to

put it on. The casket is in the rear compartments, and because it is so heavy we

should have a forklift there to remove the casket. If this is too awkward, we

can go along with a normal ramp and several men.”

“Affirmative.

We will try for the forklift.”

“Next

item,”

“Should

the Secretary of Defense and others be at Andrews on your arrival?”

“No,”

“Affirmative,”

Behn said from the ground, but

“Repeat

that to me.”

“All

the leaders of Congress, as many Cabinet members as possible at the White House

at 1830.”

“And

key members of the White House staff—[Ted] Sorensen, Bundy, et cetera,” he

trailed off, then prepared to hand the call over to the head of Kennedy’s

Secret Service detail. “Hold for Kellerman.”

“Have

helicopter to transport President Johnson and party to the White House lawn,”

Kellerman commanded Behn, who technically was his boss.

“Affirmative.”

“Have

White House cars 102 and 405 for transportation to hospital,” Kellerman said.

“I will join [agent Clint] Hill and party at the Navy hospital.”

CHAPTER 15

Two

hours after leaving behind the city that had killed Kennedy, Colonel Swindal

began his descent, swinging east over Middleburg toward the lights of DC in the

distance.

Johnson

excused himself from the group and stepped into the presidential bathroom. He

gave himself a quick shave and combed his hair, wanting to present a polished

look to the world as it gazed upon the new President for the first time. He put

on a fresh shirt, straightened his tie, and put his suit jacket back on. The man

whom critics thought too unpolished, too crude, too brusque to lead a nation

stared at himself in the mirror: Was this presidential enough?

Air

Force One glided home, over the Potomac River and a capital already in mourning,

a distant yellow light resolving into an airplane as it neared the runway and

the thousands of eyes searching the night sky for the first glimpse of the

majestic hearse. Up and down the East Coast, commercial planes circled in

midflight, diverted to clear a path for the presidential aircraft.

Colonel

Swindal eased it onto the runway, the back wheels touching down first with a

puff of white smoke, then the front, then the braking as Air Force One slowed to

a stop. Reporter Charles Roberts looked up from typing the final pool report

that would be handed out to the media. He checked his watch.

It

was 5:59 pm in

The

35th and 36th Presidents of the

A

military honor guard stood ready on the tarmac along with a Navy ambulance and a

catering truck to lower the casket from the plane.

The

press were all arranged with their microphones set, the TV lights ablaze.

Diplomats had arrived en masse, as had the public, who gathered by the thousands

outside the gates at Andrews. US government and military officials stood

uneasily in the darkness. Senators Everett Dirksen, Hubert Humphrey, and Mike

Mansfield waited near the press area. Nearby, helicopters were poised to whisk

the President, the new First Lady, and her widowed predecessor across to

“Crown”—the White House, the home that for the moment seemed to belong to

neither the Johnsons nor the Kennedys.

As

he stood to disembark, Johnson’s massive hand clenched a small piece of aboard

air force one notepaper printed with the presidential seal— his seal

now—with seven typed sentences to read to the press below, the sum total of

his staff’s wisdom during the preceding flight. He had thoughtfully edited the

statement, making changes to nearly every sentence, adding personal touches to

the cold words on the page, changing, for instance, “the nation” to

“we.”

Instead

of a joke at the podium in Austin about his charismatic leader having survived

the trip to Dallas, his final public words of the day would now be to claim

control of a tragedy in his leader’s absence and to reassure a nation that he,

Lyndon Baines Johnson—the poor boy from the Texas hill country who had

graduated from Southwest Texas State Teachers College—stood ready to inherit

command.

The

words were hard to read, and he would stumble over them, trying to decipher in

the cool

“This

is a sad time for all people. We have suffered a loss that cannot be weighed.

For me it is a deep personal tragedy. I know the world shares the sorrow that

Mrs. Kennedy and her family bears.

“I

will do my best. That is all I can do. I ask only for your help—and

God’s.”

His

plea was heartfelt. The raw power Johnson had inherited in an instant—not just

the office but ultimate control over the Polaris submarines hidden beneath the

waves, the nuclear-armed alert bombers making lazy circles over the Midwest, the

Minuteman missile crews sitting quiet vigils in their silos across the

plains—had never before been given to a man under those circumstances.

“This

is a sad time for all people. We have suffered a loss that cannot be weighed.

For me it is a deep personal tragedy. I know the world shares the sorrow that

Mrs. Kennedy and her family bears.

History’s

trajectory had been altered, and the world now waited to see what would come

next. Ahead lay the unknown pressures of the Cold War, Fidel Castro, and Nikita

Khrushchev; the drama of Martin Luther King Jr., a bridge in

The

1960s were poised to upend American life outside Air Force One. The accidental

group of passengers brought together for this flight—all the friends, all the

strangers, all the enemies, all the allies—would in the minutes and hours

ahead disperse, never to reconvene. A decade later, the same airplane, SAM

26000, would fly Lyndon Johnson home to

But

all of that lay in the future.

For

one last minute, as the stairs were brought forward, the plane and its

emotionally spent occupants stayed silent. “Let’s get everybody together,”

Johnson said, and the passengers clustered in the rear—the Kennedys closest to

the door with the casket, then Johnson, then his aides and the congressmen

behind him. Johnson reached through the crowded aisle to kiss the hand of

Kennedy aide Pam Turnure.

Then,

as those inside waited for the back door to open, a murmur passed through the

length of the aircraft: The attorney general had boarded unexpectedly through

the front door. Robert F. Kennedy, his face streaked with tears, ran through the

communications shack staffed by the exhausted radioman Sergeant Trimble, passed

through the forward galley with its depleted liquor cabinet, pushed his way

through the crowded staff area where LBJ and Jackie had stood earlier with Judge

Sarah Hughes, past the secretaries and the typewriters that just hours before

had written out the oath of office, and through to the President’s cabin.

“Excuse

me, excuse me,” he said, pushing through the knots of people. “Where’s

Jackie? I want to be with Jackie.”

Bobby

Kennedy helped his brother's widow off the plane at Andrews Air Force Base.

(Photo via MLK Library)

As

Bobby Kennedy stepped into the President’s cabin, the new President of the

His

voice weighed down with emotion, Lyndon Johnson greeted RFK simply: “Bob.”

But

the attorney general never broke stride, pushing right past his new boss, past

everyone until he reached his brother’s widow, standing next to the bronze

casket with the broken handle.

Her

brown eyes turned toward him.

“I’m

here,” he said.

“Oh,

Bobby,” she said.

They

hugged.

And

the rear door of Air Force One opened.